[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down]

No one really talks in Youth, at least not the way that real people do; rather, the characters in this wonky mess of a picture speak in epiphanies, in long soliloquies that expound on larger topics and themes. A movie can get away with a couple of these moments if they earn them, yet to construct a picture out of them en masse is folly, and it’s the trap that Youth has fallen into. And despite some earnest attempts to patch together a metaphorical framework for things via some outlandishly surrealist sequences, writer-director Paolo Sorrentino tells more than he shows, and wastes some damn fine performances from his cast.

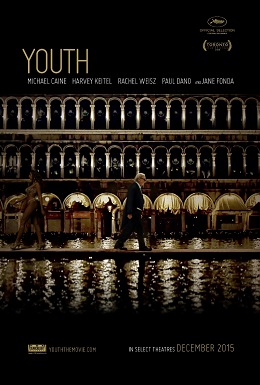

The film opens with retired composer and conductor Fred Ballinger (Michael Caine) relaxing in the garden of a Swiss resort and spa. An emissary from Queen Elizabeth II is there with Fred, and asks him to conduct one of his most famous pieces for a special event for the Queen and Prince Philip. With enigmatic finality, Fred refuses, yet the film moves on without following back up on this thread for quite some time, and concerns itself instead with magical realism vignettes that dance around the periphery of the picture without adding anything to it. The most consistent and stable portion of the narrative follows the life-long friendship between Fred and his film director friend, Mick Boyle (Harvey Kietel), who is also staying at the spa. As chance would have it, Fred and Mick’s kids are married to each other, and one of the other plotlines of Youth revolves around the turbulence of that relationship. There’s also a few tangential threads about a one-hit wonder actor, Mick’s pre-production meetings with his newest film’s writers/cast, and a mysterious, famous fat man: all of them guests of the Swiss spa.

Yet as far as the halfway mark in its 123 minute runtime, it’s hard to say what Youth is really about. As already mentioned, there are a lot of epiphanies in the film, yet they are lazily tossed at the audience with all the subtlety of a 90s-era Kevin Smith monologue. Stylistically, Youth goes for a Fellini-meets-Wes Anderson-meets-Coen brothers flavor, yet fails to develop its foundation in a way that might support such lofty ambitions. You see, the movie is all dessert without any vegetables, and despite the deep reflections and fully developed treatises of self-reflection of its characters, Youth is little more than an exercise in golden-years reflection cinema. It tries to say something about the fading optimism of youth, and the pessimistic finality of old age, yet except for the moments when the characters flat-out tell the audience about this (Kietel’s telescope monologue in this vein is just embarrassing), the picture never really bears it out.

There’s a lot of moving pieces in the picture, as well as a couple interesting flashes of narrative that almost hold one’s attention, yet Youth doesn’t seem all that certain what it wants to be about. Instead, the film wades in a pool of quirky characters that tell you exactly what they are thinking, and advance their portion of the scene to an almost-funny climax that rarely pays off. Caine and Kietel do fine work, as do Paul Dano and Rachel Weisz in supporting turns as the one-hit-wonder actor and Fred’s daughter, yet they speak more than they act. The writing and rehearsal of the movie Mick and his production team are working on flirts with some level of parity with the narrative of Youth as a whole, yet like most things in this picture, the idea is half-baked and poorly-formed.

Visually, there’s a lot to admire about Youth, as its setting in the Alps lends itself to some positively stunning shots. The surrealist moments aren’t without their charms from a cinematic standpoint, yet again, it’s all polish without any substance. There’s a lot of regret and longing in this film, but only a few substantial moments where characters earn the leeway to wallow in it. Indeed, it is hard to trust a character who tells you everything you need to know about them rather than discovering it for yourself, so these sentimental monologues about self-discovery seem cheaply purchased, and disingenuous. In other words, if it walks like a duck, and talks like a duck, audiences rarely jump out of their seats when the quacking character in question turns out to be a goddamned duck.

Even if we did care about Fred or Mick’s missed opportunities, or their reflections on long lives haphazardly lived, what we know about them comes only from what they tell us. Thus, we aren’t taken on a journey in Youth, we don’t learn anything: we’re told what is supposed to be known, and bombarded with over-the-top visual stimulus to fill in any blanks. What the audience is left with, then, is a visual and thematic hodge-podge of several competing ideas and characters: none of whom get the necessary time to develop into anything significant. Although there are discernible arcs and some level of growth for a few of the characters, it is all so on-the-nose and force-fed that the whole affair comes off as decidedly manufactured and plastic.

Comments on this entry are closed.