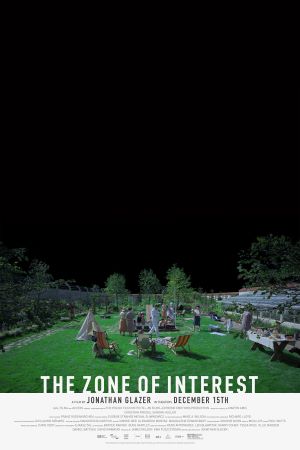

[Rating: Rock Fist Way Up]

In Select Theaters Friday, December 22

There are so few movies of this caliber, where every decision is correct from stem to stern, where there are no misses, wasted scenes, moments, or even gestures. Like a baseball player on the mound throwing every pitch in their arsenal with devastating precision, writer/director Jonathan Glazer uses all the tools at his disposal with exacting control, getting out after out with each thoughtful set piece. This comprehensive approach is necessary, too, because The Zone of Interest speaks volumes by working along the edges of its subject, and in so doing reveals as much about the topic at hand as any that confront it head-on. Haunting, stark, and honest in ways that movies rarely dare to be, Glazer’s film is as merciless as its featured characters.

It all seems so idyllic at first, too. The opening scene shows a family relaxing by the side of a gentle stream as the children splash each other and the parents look on without a care in the world. It’s faint at first: the sound of machinery’s deep, low grinding, or the hiss of a train’s brakes, but it is there. The echoes persist, and before long they begin to draw the audience’s focus away from the halcyon images to the terrible truth buttressing them: the explicit nature of which is made clear at the 10-minute mark.

It’s at this point that the viewer gets their first look at the barbed wire-topped fence in the background, and the smokestacks operating at full tilt behind them. The word “Auschwitz” isn’t spoken right away, yet there’s enough clues in the opening minutes to piece together the who and the where of things as camp commandant Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) and his wife/children go about the normal business of life as a genocide unfolds right beside them. As the family receives visitors, tends to their garden, and plans for the future, the oppressive chorus of barking dogs, screaming victims, and gunshots resonate in the distance.

Glazer has gone out on one hell of a limb with his approach by deciding to focus on the perpetrators of the crime rather than the victims, and more still: to highlight not the crimes, but the lives along the periphery of them. This would be like making a movie about Pontius Pilate’s in-law troubles right after his move to Judea, and in the hands of any other director the results would likely be just as laughable or misguided as that comp. Again, though, Glazer is throwing a perfect game with all of this by combining subtle character work, precise set decoration, a haunting score, and singular (unrivaled) sound design to tell this story.

It works because this isn’t a narrative dedicated to the murders, but rather what needs to happen in order for such atrocities to be carried out. Whether it is the camp commandant’s wife (Sandra Hüller) joking about finding diamonds in toothpaste, his boys role-playing murder, or just a persistent stomach ache without a physical source: the evil seeps in and stains everything it touches. And while it would have been easier to show these people as one-dimensional monsters shrugging off their complicity in wholesale homicide, The Zone of Interest insists that the reality is far more insidious.

The soundtrack of Auschwitz haunts viewer and characters alike, but it hasn’t broken those onscreen (except for the visiting mother-in-law, maybe), and that’s the point. It’s almost easier to assign the perpetrators the now-classic distinction of the banality of evil, yet that too lets them off the hook in a way that Glazer and his film won’t endorse. The crimes didn’t bounce off of these people as they might a switchboard operator just punching buttons and plugs. No, folks like Höss and his wife knew what they were doing, were changed by it, and kept doing it anyway.

At Nuremberg (not seen here) they assuaged their collective conscious by their defense that they were just following orders, yet The Zone of Interest supposes that this too was a fiction: that the screams and the crackle of gunshots made an impact even then. This makes them doubly culpable for their action and inaction alike and invites the audience to understand why that’s the case in scene after devastating scene. As the glow of the chimneys turn black midnight skies into bright orange day, waking the Höss family, the audience understands; as Mrs. Höss pleads with her husband to let the family remain at Auschwitz during his upcoming transfer for the mental health of the kids, the audience understands; as the youngest family member cries almost non-stop from the opening minute to the last, the audience understands.

Everyone in this orbit came out of the ordeal a changed (or dead) person, and there’s not enough banality in the world to explain this away. Glazer clears out room for each of these moments and allows the combination of acting, dialogue, lighting, and (of course) sound to guide the audience through all of this, never wasting a second of any scene.

Hüller and Friedel are both magnificent in the lead roles, comprehensive in their presentation yet always under-selling their moments in service to the broader thematic narrative. Yet this movie is the definition of success via the sum of one’s parts, as every component of the production adds a layer to its overwhelming truth. Glazer’s management of all departments, in particular the sound design, is a credit to his skill as a filmmaker and to what’s possible when uses all the tools of the medium to perfect effect.

Comments on this entry are closed.