[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

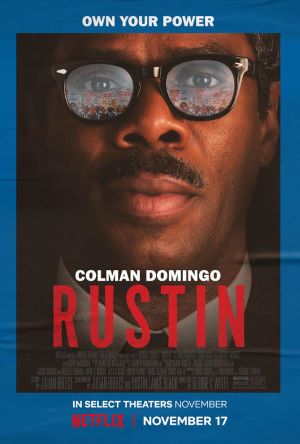

Streaming on Netflix November 17

A bundle of cinematic contradictions as nuanced and contrary as its eponymous subject, Rustin is a great story stuck inside of a mediocre script. It’s a fun watch despite the heavy material, and is aided in no small part by crisp production design and pacing (director George C. Wolfe and cinematographer Tobias Schliessler shoot the hell out of this this thing), along with an all-star cast turning in career-best performances across the board. This gives the film everything it needs to succeed…well…everything except faith in its audience to digest the difficult bits.

Most of Rustin takes place during the summer of 1963, in the lead up to the March on Washington that saw Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (Aml Ameen) give his “I Have a Dream” speech. The movie portrays the march as the idea of Civil Rights activist Bayard Rustin (Coleman Domingo), who harnesses the organizational power, money, and resources of the disparate yet related social and political action groups to bring it to life. And while the leaders of the various Civil Rights organizations recognize Bayard’s abilities for headline-grabbing action and change, they struggle with his political liabilities as a somewhat “out” gay man.

Bayard forges ahead with his vision regardless and works to patch up broken relationships with movement leaders like Dr. King, labor organizer A. Philip Randolph (Glynn Turman), NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins (Chris Rock), and about a dozen other volunteers, politicians, activists, and donors that have a vision for the event. In the process, Wolfe and the screenplay fold in some of Bayard’s pre-1963 history to give a more complete picture of the man by way of his earlier organizational victories and failures: both of which inform his approach to the march in ’63. Rustin also takes the time to outline the ways Bayard’s personal life and relationships color his outlook on the past, present, and future (to sometimes mixed results).

On the one hand, the film should be commended for exploring the faults in its lead instead of beatifying him wholesale, as it makes Bayard more human, relatable, and certainly no less admirable. The fact that he struggled with his sexuality and had messy relationships enrich an already fascinating text when exploring the man and his life’s work, yet the screenplay seems happy to just introduce these ideas rather than contend with them. A difficult reckoning with Bayard’s lovers, Tom (Gus Halper) and Elias (Johnny Ramey), is built up throughout the course of the movie, yet it comes and goes with little impact despite its central place in the narrative.

Bayard must have had a difficult time juggling his personal life with his public-facing responsibilities, yet besides its willingness to acknowledge that this was a thing, Rustin never confronts how this affected the man. Like a handful of sitcom episodes stitched together, the movie introduces mini conflicts throughout only to reset after each in service to the main narrative (in this case, the march). Domingo is talented enough to inform the audience what these battles look like in the moment, yet as soon as these scenes are done the movie moves on via its conflict-of-the-week format.

Like the extraneous dialogue that weighs down so many of these scenes, Wolfe and the script don’t seem to have faith in the audience’s ability to handle more than one complex idea at a time lest it is made explicit. An exchange late in the movie illustrates this to a T, when one impressed organizer asks, “How does so much get accomplished in such a short amount of time?” To which a volunteer responds, “By working 12 to 15 hours a day every day and because of Bayard.” Film is a visual medium: why this has to be said instead of demonstrated (as it mostly is anyway) is part of the reason this one doesn’t always land.

And yet despite these clunky exchanges and narrative half-measures, Rustin is often inspiring and invigorating. Watching Bayard harness the full power of his organizational and logistics toolkit is both fun and fascinating and serves as a great lesson about what goes on behind the scenes when history is made. The movie also goes out of its way to highlight all the different subsections of society that made the march possible, from the NAACP’s old guard, student organizers, union reps, community activists, academics, police officers, celebrities, and even serving politicians like John Lewis (Maxwell Whittington-Cooper).

The supporting cast plays up to or near Domingo’s level, who sets the tone for each scene with his swagger, attitude, and diction. Turman and Rock do great work as the opposing poles between which Bayard must function, and CCH Pounder comes in late as the legendary activist and educator Dr. Anna Hedgeman in a role that focuses the organizational piece of narrative. This really is the Coleman Domingo show, though, and he more than delivers as the charismatic engine that fueled the Civil Rights vehicle during the mid-20th century. Sure, the script falls short of the mark when it blocks the audience from navigating the trickier portions of Bayard’s life (as well as the faith to let them work some things out on their own), yet Rustin is nevertheless a fitting tribute to a man more than worthy of some credit for his work behind history’s curtain.

Comments on this entry are closed.