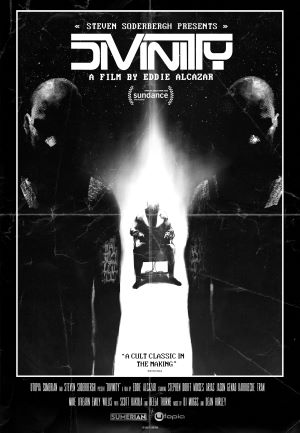

(Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down)

In Theaters November 3

An anemic sci-fi yarn that stretches 40 interesting minutes into 80 intolerable ones, Divinity has a lot of ideas but precious little direction. Less of a movie and more like a pulsating synth beat imbued with visual presence, the film by writer/director Eddie Alcazar leans into world building at the expense of character. Vaguely exciting and bold enough to let the audience discover the interesting bits all on their own, Divinity never provides enough story to assemble a coherent narrative, yet also lacks any kind of cinematic rhythm which would allow that not to matter.

As for the story, it comes in pieces starting with a video diary from scientist Sterling Pierce (Scott Bakula), whose late-20th century research led to the discovery of a serum, Divinity, that prolongs life and enhances physical capabilities. Sterling is long dead, however, and one of his now-adult sons, Jaxxon (Stephen Dorff), has transformed 21st-century society with his mass production of the drug. The precise nature of the chemical’s composition is a secret, however, and the arrival of two space brothers (angels?) threaten to uncover Jaxxon’s secrets when they invade the man’s house in the dead of night.

These brothers (Moises Arias and Jason Genao) look/act alike, don’t identify each other with names, and are driven by an unassailable need to incapacitate Jaxxon and dose him with a steady, uncut Divinity drip. During this captivity, a sex worker Jaxxon had scheduled for an encounter arrives and becomes smitten with the brothers, thinking they are the ones who contracted her. This woman, Nikita (Karrueche Tran), provides more background about the world and the way Divinity has altered the course of humanity, and becomes tangled in the drama unfolding between the brothers, Jaxxon, and a gaggle of guests set to arrive for the captive man’s birthday party.

Story-wise, that’s pretty much it. There’s a big reveal at the end that pulls the curtain up on what’s actually going on with the development of the drug, but (no spoilers) it’s nothing groundbreaking or gasp-worthy. Divinity does tie up a few loose ends that explain the appearance of a coterie of desert nymphs led by Bella Thorne, yet any good vibes that arise from competent story symmetry are dashed by a Claymation finale that looks like a proof-of-concept VFX reel. And for a film that relies so heavily on atmosphere crafted via a combination of score, set design, and visuals, Divinity never corrals any effectively.

Alcazar presents the story in black and white yet does little with the format except to hide in shadows what the budget couldn’t paper over. Although this old Hollywood trick is effective up to a point, the monochrome presentation doesn’t contend well with the shadows and, even in daylight, obscures the facial reactions of the actors and confuses the depth of field. This leads to a flat, muddled viewing experience that is more than ugly: it’s boring.

Early Lynchian visuals give way to 80s dystopia tropes that are more in line with Carpenter (They Live), Verhoeven (Robocop), Cronenberg (Videodrome), and Gilliam (Brazil), yet unlike these directors and those movies, Alcazar abandons the development of his characters in service to more world building. The video diaries and portions of Jaxxon’s captivity flesh out the villain’s motivations to a certain extent, and Nikita gets some development (albeit in service to the larger story), yet the brothers remain more or less anonymous and formless throughout.

Seemingly the engine of the story, the audience knows next to nothing about who/what they are, where they come from, and what’s driving them to accomplish their goal(s). What’s more, by never identifying or differentiating them either by name or appearance, the movie limits how much the audience can (or would be willing to) connect with them and what they’re about. Carpenter, Cronenberg, Verhoven et al understood that it wasn’t enough just to be weird and interesting: movies need character and buy-in, both of which are lacking in Divinity.

The script and the presentation aren’t the only things holding the audience at arm’s length, though, with the acting having a big hand in that as well. The performances swing hard between campy/cartoonish and lifeless, which does this cast no favors and further limits how much an audience can connect with it all. Bakula provides some gravitas and humanity, proving once again that the actor is incapable of turning in a bad performance, but he’s the high-water mark, here.

Weighed down by an overabundance of foundational narrative that drowns any character development, and hampered further still by visuals that don’t work and performances that don’t land, Divinity is an organized collision of bad choices and even worse execution. There’s an interesting story, here, and an earnest attempt at social commentary by connecting ideas related to societal decay with humanity’s sacrifice of its future for short-term gains, yet it all falls flat. An intriguing first draft of what could one day become a good movie, to get there Divinity would need a miracle even the two space-angel brothers would be hard pressed to deliver.

Comments on this entry are closed.