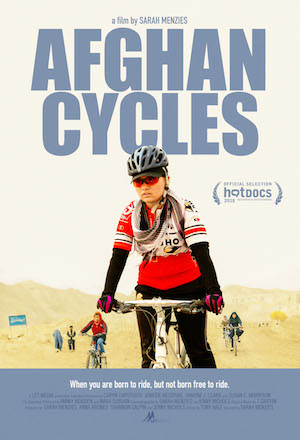

Inspiring and heartbreaking all at once, Afghan Cycles is a window into a world most will never know, and many could never hope to survive. It follows a group of young ladies who are trying to establish a new athletic culture in Afghanistan, one where women feel comfortable pursuing whatever activities appeal to them. And while the story is compelling and inspiring, the documentary’s narrative is somewhat two-dimensional and inconsistent, making for a scattered viewing experience.

Director Sarah Menzies opens her documentary in France, where a woman, Frozan, reflects back on her time living in Afghanistan. Four years previous, in 2013, she had been a part of the nation’s newly re-formed women’s cycling team, yet this is clearly a part of her past, not present. More than a decade removed from Taliban rule, Frozan explains that women in Afghanistan struggle with violent misogyny and a male-dominated culture that views the simple act of leaving the house as scandalous.

Afghan Cycles jumps back to 2013 at this point, when Menzies’ film crew was in Afghanistan to document Frozan and her teammates training for international competitions. The audience is introduced to aspiring cyclists Masoma, Mariam, Zahra, and a handful of other brave women who endure taunts, hurled rocks, and even bumps from vehicles when going for bike rides. Despite the fact that these ladies cover their arms, legs, and head per the local custom, the act of cycling is seen as incendiary and provocative. Until recently, most women in Afghanistan were not able to attend school, engage in politics, or participate in any sporting activities. Any independent female activity that involves autonomy or agency in Afghanistan is seen by many as an affront to the marginalized religious fanatics responsible for much of the region’s violence.

Afghan Cycles jumps back to 2013 at this point, when Menzies’ film crew was in Afghanistan to document Frozan and her teammates training for international competitions. The audience is introduced to aspiring cyclists Masoma, Mariam, Zahra, and a handful of other brave women who endure taunts, hurled rocks, and even bumps from vehicles when going for bike rides. Despite the fact that these ladies cover their arms, legs, and head per the local custom, the act of cycling is seen as incendiary and provocative. Until recently, most women in Afghanistan were not able to attend school, engage in politics, or participate in any sporting activities. Any independent female activity that involves autonomy or agency in Afghanistan is seen by many as an affront to the marginalized religious fanatics responsible for much of the region’s violence.

In Afghanistan, life is already dangerous, what with the daily threat of suicide attacks, ISIS infiltration, or Taliban intimidation. Afghan Cycles convincingly suggests that for these women to go out and actively court controversy by living their best lives is a staggering display of bravery. This is reflected in the way these women appear on-screen, with only their first names provided, for threats of reprisal for engaging in this kind of lifestyle are very, very real. The women understand this, too, and in their talking-head confessionals, pride and fear comingle in equal parts. To cycle as a woman in Afghanistan is to literally risk one’s life, yet the consistent theme throughout all the conversations with Frozan et al is how much this simple act means not just for them, but for the betterment of their communities.

This first portion of Afghan Cycles is confined to an exploration of this duality. Frozan’s mother loved to cycle as a youth, yet lost that privilege under the Taliban; this makes her daughter’s struggle all the more profound for the woman, and only further inspires Frozan. Young girls growing up in Afghanistan also look up to these cyclists as a harbinger of expanded opportunities for the coming generation, and Frozan and her teammates take this responsibility seriously.

Yet as the documentary continues, it goes a bit flat. Masoma, Mariam, and Zahra all speak to the same things Frozan mentioned vis a vis their motivation for riding, and what it means to not just them, but the country. It’s a note Afghan Cycles hits again and again, and after a while, it feels a little repetitive. It also doesn’t set up the most dramatic portion of the documentary’s story: Frozan’s escape to France, which is teased by Menzies in the opening minutes. The first two-thirds of this documentary is all about how proud these women are to cycle in Afghanistan, and what that means to them (Frozan included), yet this stands in stark contrast to what’s set up in the last third. A failure to introduce this simmering conflict early on gives Afghan Cycles a mismatched feel: like Menzies started making one documentary, only to discover a different one part of the way through.

Yet as the documentary continues, it goes a bit flat. Masoma, Mariam, and Zahra all speak to the same things Frozan mentioned vis a vis their motivation for riding, and what it means to not just them, but the country. It’s a note Afghan Cycles hits again and again, and after a while, it feels a little repetitive. It also doesn’t set up the most dramatic portion of the documentary’s story: Frozan’s escape to France, which is teased by Menzies in the opening minutes. The first two-thirds of this documentary is all about how proud these women are to cycle in Afghanistan, and what that means to them (Frozan included), yet this stands in stark contrast to what’s set up in the last third. A failure to introduce this simmering conflict early on gives Afghan Cycles a mismatched feel: like Menzies started making one documentary, only to discover a different one part of the way through.

The inability to connect these two stories in a narratively cohesive way is where this effort goes off the rails a bit. What had been a story about women overcoming social stigmas and physical danger to pursue their passions transforms into a lesson about protecting one’s best interests, and abandoning idealism for security. If this is a deliberate attempt to confront or challenge the idealism of the first portion of Afghan Cycles, it just isn’t pulled together in a satisfying why. The story is interesting, and the struggle is engaging and easy to sympathize with, but as a documentary effort, it feels uneven and incompatible with itself.

Playing this weekend at the Seattle International Film Festival, Afghan Cycles is a very interesting look at a group of women who deserve all the attention and respect in the world. Thematically inconsistent at times, there’s two portions of this movie: both of them considerate, important, and very well-made. Unfortunately, they have some trouble merging together into a consistent and cohesive narrative that does justice to them. This shouldn’t keep a person from going to see Afghan Cycles, but it is a possible reason why that same person may leave the theater wanting just a little bit more.

Comments on this entry are closed.