In their best form, amateur and professional sports offer people the opportunity to come together for a common cause, the team. Rich or poor, Jew or Gentile, black or white: organized athletic competition gives fans and players alike an avenue through which barriers can be broken and new bonds can be formed. Hollywood has exploited this trope ad nauseam, with nearly every sports-themed movie playing up the ragtag-misfits-that-come-together scenario to death. Yet this is for a good reason, for it represents the very best that the human experience has to offer, i.e., the casting aside of prejudice and the elevation of community. Sports actually do this; games involving balls and sticks do this, which seems mad considering geopolitical maneuvering and war sometimes can’t.

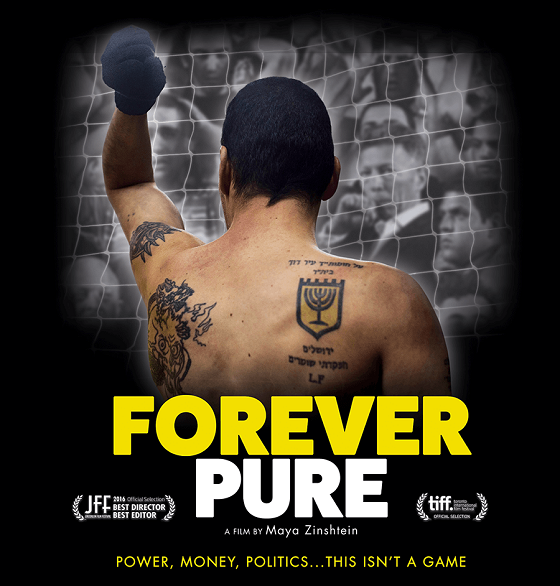

What happens when sports fail to bridge a cultural gap, however? That’s the question director Maya Zinshtein asks with her insightful and crushing documentary, Forever Pure, which concerns itself with one of the most controversial seasons of Israel’s most popular soccer club. This team, Beitar Jerusalem F.C., is like the Boston Red Sox, Dallas Cowboys, and Manchester United all rolled into one…and on steroids. Beitar’s connection to the Jewish community in Jerusalem goes back decades, and as one person states, the team, “became a political symbol for second-class Israelis…it was the team of the underprivileged.”

Since Israel’s working-class identifies so closely with the team, and since it has the largest and most passionate fanbase, Beitar has evolved into a powerful political tool that can be used to influence policy or political reform. This is why Russian-born billionaire Arcadi Gaydamak purchased the team in 2005, a fact Gaydamak is perfectly frank about when speaking on-camera in Forever Pure. He remarks that he bought the team as an investment opportunity, and also as a way to increase his visibility in advance of a mayoral run in Jerusalem. Yet when Gaydamak’s political aspirations failed to come to fruition in 2008, his interest in the team seemed to disintegrate.

By late-2012, when the documentary starts following around Beitar, the team and its fans have suffered through several losing seasons, and Gaydamak appears ready to abandon the team. Before doing so, however, the club owner makes a shocking announcement: he’s signing two Muslim players to Beitar. Widely considered to have the most racist, anti-Muslim fanbase in the league, the club’s supporters live up to their reputation and proceed to lose their goddamned minds. Gaydamak admits that this reaction was always the intention, and he does little to calm matters.

Beitar team captain and goaltender Ariel Harush is vocal in his support of his two new teammates, as is the coach, GM, and several of the other players. Yet this isn’t just a group of supporters firing off angry tweets and Facebook posts (though there’s plenty of that), this is hundreds, if not thousands of people getting in the faces of players, picketing their houses, sending death threats, and firebombing facilities. Beitar players and personnel who do nothing more than stand up for their teammates and denounce racist rhetoric become as hated as the two Muslim players themselves, and before long, these tensions lead to divisions within the locker room.

One Beitar player, Ofir Kriaf, publicly comes out against the club’s decision to bring the new players on, which only further encourages the most vocal “fans” to pursue their campaign of intolerance. These club supporters call for the sacking of any teammate or club official that supports the new players, which makes it very difficult for any fair-minded people to pursue the moral and ethical high-ground. Despite death threats and boycotts, the team’s coach and captain stick to their principles, and continue to encourage unity and tolerance. Tensions continue to mount as a result, both on the field and off, and by the end of the season Beitar is in the cellar.

Forever Pure is a powerful look at the intersection of 21st century race, politics, class, mob rule, and sports in a region that is as volatile in these areas as anywhere else in the world. Content to sit back and allow the story to unfold, and for audiences to draw their own conclusions, Zinshtein and her film succeed because they never try to push a narrative, or a conclusion. The two Muslim players, Gabriel Kadayev and Zaur Sadiev, say everything they need to with their blank, wounded faces as they pass throngs of people shouting anti-Muslim slurs. They seem to silently deflate as the documentary and the season progresses, and even a clutch goal by Sadiev during an important match does nothing to stem the tide. Indeed, if anything, it makes Beitar’s fans even angrier, and rather than cheer for their team’s success, they walk out in protest.

The whole thing is startling to watch, and flies in the face of expected conventions regarding sports and its ability to unify. Despite the fact that a person’s religion has no bearing whatsoever on their ability to kick a ball, Beitar fans take hold of their hatred and prejudice like a man clinging to life on the side of a skyscraper. Kadayev and Sadiev have the potential to help the team succeed, yet their status as Muslims not only drive fans away from the club, but compel club supporters to attack anyone who dares stand up for the men. How this all unfolds says a lot about the fans, but even more about racially-influenced geopolitical conflict in the age of ISIS, Donald Trump, and the alt-right.

It’s almost enough to make a person lose hope in humanity, and our ability to grow beyond the savage prejudices that led to the murder of millions less than a century ago. Yet for every Ofir Kriaf, there is a noble counterpart, like Ariel Harush. And for every Beitar, there is the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers, or the 1995 South African Springboks. Currently playing at this year’s Seattle International Film Festival, Forever Pure doesn’t have any easy answers, and is devoid of a central message, except, perhaps, that when it comes to tolerance, the 21st century has a long way to go to distance itself from its predecessors.

Comments on this entry are closed.