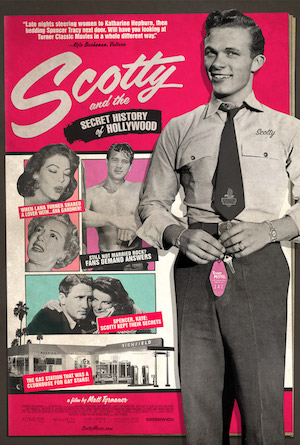

A commendably complicated documentary featuring a subject that is both an open book as well as a sealed vault, Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood walks the fine line between intriguing and tragic.

A cinematic adaptation of the eponymous Scotty Bowers’ 2012 tell-all book, the film uses Scotty’s story to speak to a larger narrative about Hollywood optics and mid-20th century LGBT culture. Director Matt Tyrnauer does his best to shape a responsible, interesting narrative out of roughly 70 years of stories, yet like the hoarded houses and storage spaces Scotty keeps and picks through in the doc, one feels like the effort only scratches the surface.

Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood moves in a mostly linear fashion, following present-day Scotty (who is now in his early 90s) as he goes to book signings and tends to his various cluttered “estates” while recounting the story of his youth. A mid-westerner by birth, Scotty was in combat as a Marine in World War II, then settled down in Hollywood after the war like countless other veterans. Scotty had very liberal ideas about sexuality, though, and didn’t hesitate when actors from the nearby studio lots began frequenting the gas station where he worked, obliquely propositioning him. Within days, he found that he was the go-to booty-call for Hollywood’s gay community, and it occurred to him that there was an opportunity in all this action for other like-minded young men.

For $20, Scotty and his friends “tricked,” using the gas station as a base of operations. Whether the client was a movie star, a set dresser, a travelling business person, a man, or a woman: it didn’t matter so long as they had $20. Scotty participated, but most importantly, he made introductions. Yet this match-making was a free service, and one Scotty did gladly and in a way that eschews the traditional “pimp” role. As he tells it, anyway, Scotty was just about making people happy, and getting his own rocks off when he could. If Scotty could make a little money himself while helping his friends do the same, then no one was in a position to complain.

Through the connections he made in the late-40s and 50s, Scotty claims to have had sex with and/or arranged hook-ups for just about every Hollywood icon of the era who was rumored to be gay or bisexual. Bette Davis, Cary Grant, Randolph Scott, George Cukor, Spencer Tracy, Katherine Hepburn, and Cole Porter are just a few of the names he drops when speaking about personal relationships and interactions. It all seems a bit fantastical at times, yet through interviews with former hustlers, Hollywood biographers, and industry luminaries like Peter Bart, it all seems plausible, too.

Through the connections he made in the late-40s and 50s, Scotty claims to have had sex with and/or arranged hook-ups for just about every Hollywood icon of the era who was rumored to be gay or bisexual. Bette Davis, Cary Grant, Randolph Scott, George Cukor, Spencer Tracy, Katherine Hepburn, and Cole Porter are just a few of the names he drops when speaking about personal relationships and interactions. It all seems a bit fantastical at times, yet through interviews with former hustlers, Hollywood biographers, and industry luminaries like Peter Bart, it all seems plausible, too.

Even so, once the audience moves through the salacious gossip about who was screwing who, and how, one finds a dark underbelly attached to Scotty and this little universe. Many have questioned the ethics of “outing” a person after death, and it is an issue Scotty tackles head-on. He claims that the stars he’s written about were mostly “out” to their close friends and family, and argues that revealing their proclivities in this more enlightened century doesn’t matter because there’s nothing wrong with being gay.

This discussion about how Scotty has removed the agency from countless people is touched upon, but as an issue, it is wand-waved away. Even more disconcerting is the relatively small amount of time allotted to Scotty’s early years, where he confides that he was molested as a young boy, which led to a childhood defined by his willingness to prostitute himself to older men (including dozens of priests). Tyrnauer presses Scotty on these points, saying that most people would consider this a serious form of abuse, and should have been addressed via therapy years ago. Yet Scotty again brushes off such concerns, and claims that if someone enjoys something, as he did, then it is not abuse. The certainty with which he makes these claims is chilling, and points to a much more interesting (and troubling) story that Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood largely dodges.

If Scotty is this casual about his own abuse, it makes one wonder about what he dismissed when he was a relationship “arranger” back in his heyday. In the #MeToo era, it is impossible to separate Scotty’s stories from those about Hollywood’s infamous casting couch (which has never had a set sexual orientation). Scotty says that all of the dates he arranged were between consenting adults, which if true seems like a harmless thing, yet Hollywood is full of stories of the powerful exploiting the dreams of “nobodies” looking for a way into the industry. The fact that this cruel reality is never addressed is curious, especially in light of Scotty’s stance on abuse, and leaves something of a hole in a narrative that seems so enlightened otherwise.

If Scotty is this casual about his own abuse, it makes one wonder about what he dismissed when he was a relationship “arranger” back in his heyday. In the #MeToo era, it is impossible to separate Scotty’s stories from those about Hollywood’s infamous casting couch (which has never had a set sexual orientation). Scotty says that all of the dates he arranged were between consenting adults, which if true seems like a harmless thing, yet Hollywood is full of stories of the powerful exploiting the dreams of “nobodies” looking for a way into the industry. The fact that this cruel reality is never addressed is curious, especially in light of Scotty’s stance on abuse, and leaves something of a hole in a narrative that seems so enlightened otherwise.

Tyrnauer should be commended for leaving these moments in the documentary, as he could have just as easily skipped this, or the obvious compartmentalizing Scotty does to hide the pain he so clearly feels despite his relentlessly optimistic demeanor. The death of his older brother, daughter, and common law wife over the years seems to weigh heavily on the man, and he makes no apologies about the fact that he uses sex as a coping mechanism. As fascinating as it is to hear about Hepburn and Tracy living a lie, or J. Edgar Hoover in drag, an exploration of Scotty as a damaged, flawed human being who nevertheless brought a lot of joy into people’s lives would be infinitely more interesting.

Opening this week, Scotty and the Secret History of Hollywood is a captivating peek into the closeted days of Hollywood, and one man’s connection to a scene that has all but vanished. Discussions about the optics of the old studio system and what it was like to be gay in the more repressed mid-20th century are intriguing, and is fun gossip fodder for fans of Hollywood’s classic era. Yet this is all little more than a distraction from a much more interesting story that the documentary side-steps, one connected to a social reckoning in Hollywood that transcends everything laid out here. The documentary is a good one, to be sure, but it is hard to escape the nagging suspicion that it was a few moves away from being something very special.

Comments on this entry are closed.