Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is the most recent entrant in a spate of dying teen and young adult films. These films typically rely on the compressed mortality of a secondary character to either motivate the main character to live more vibrantly, or to appreciate the life that they have and the people that surround them. This growing genre is usually a subset of the teen romance, and can be traced back to the tragic love stories of ancient Greece.

So what does Me and Earl and the Dying Girl have to say that has not already been said many times over? I suggest that it has a few nuances that are interesting and make it a welcomed newcomer, but still holds onto some worrisome tropes that keep it from rethinking the genre in a meaningful way.

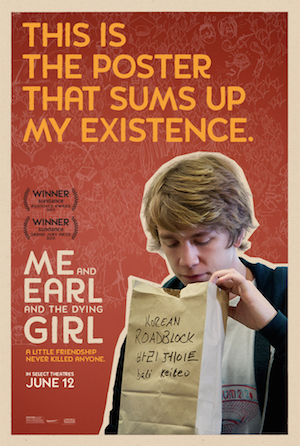

Greg (Thomas Mann) is a senior in high school. He is a social introvert, who interacts with his peers just enough to get along with everyone, while still being almost completely ignored. His only friend is Earl (RJ Cyler), a neighborhood companion who Greg refuses to refer to as anything but a coworker, a designation Earl receives because he and Greg make films together.

When a school acquaintance, Rachel (Olivia Cooke), is diagnosed with cancer, Greg’s mother (Connie Britton) insists that Greg spend some time with her. The ensuing friendship helps Greg understand what he’s been missing out on by not allowing himself to form any real connections with anyone around him.

When a school acquaintance, Rachel (Olivia Cooke), is diagnosed with cancer, Greg’s mother (Connie Britton) insists that Greg spend some time with her. The ensuing friendship helps Greg understand what he’s been missing out on by not allowing himself to form any real connections with anyone around him.

This is not a wholly new take on this type of story, but it does a few things very well.

It is (mostly) honest, awkward and insensitive in regards to death and the terminally ill. It achieves this through subtle performances and masterfully constructed visuals. Greg does not know how to respond to Rachel’s illness. He says things about dying then over apologizes for saying things about dying.

In one of Me and Earl and the Dying Girl’s more compelling moments, Rachel tells Greg that she going to stop treatment. Greg at first laughs it off, then gets confused, then angry. Thomas Mann gives nuance and variation to Greg’s character. Because of the performance, we can see Greg’s thoughts as he tries to resolve the conflicting emotions he is feeling.

In one of Me and Earl and the Dying Girl’s more compelling moments, Rachel tells Greg that she going to stop treatment. Greg at first laughs it off, then gets confused, then angry. Thomas Mann gives nuance and variation to Greg’s character. Because of the performance, we can see Greg’s thoughts as he tries to resolve the conflicting emotions he is feeling.

Olivia Cooke allows her silent stoicism to speak for her. On Rachel’s face we can see a strength tested by her fears, the hurt she feels at Greg’s barbed words and her compassion for him.

Director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon and cinematographer Chung-hoon Chung use the visual frame to accentuate this desperate awkwardness. Greg is framed in the upper right in the distance, while Rachel is on the left and forward. Both look towards the viewer, unable to engage each other directly. Rachel’s close up looms in the foreground, which allows her silence to carry and the viewer to read her stoic expression more clearly. Greg is more animated, but he is also tiny and trapped in his small corner of the screen as he flails against the inevitable.

No one responds to death correctly. There is no acceptable response. Our individual mortality and the mortality of others are confusing and sad. It is refreshing to see characters react directly and with raw emotion to the news that one of them will die, and far sooner than expected. This is an ugly moment and it is allowed to be just that.

No one responds to death correctly. There is no acceptable response. Our individual mortality and the mortality of others are confusing and sad. It is refreshing to see characters react directly and with raw emotion to the news that one of them will die, and far sooner than expected. This is an ugly moment and it is allowed to be just that.

Where Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, and so many other films that deal with dying teens, fails is in its resolution. The film is buttoned up too neatly. The lessons each character was meant to learn are far too clear and learned too well. All questions are answered. Everything in the end is clean and tidy.

This rings false. Anyone who has faced the death of a loved one knows that resolution comes in fits and starts. The resolution of one day is undermined by the questions of the next. Death creates a raw vacuum, and the only real consolation comes in the burden shared by all who feel the loss.

It is also troubling that like so many other stories in the dying teen genre, a young woman is used to motivate a quirky, disconnected young man. Her death is just what he needs to overcome his inhibitions and learn that life is about caring for those around you. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl does avoid a direct romance between Greg and Rachel, but just barely.

It is also troubling that like so many other stories in the dying teen genre, a young woman is used to motivate a quirky, disconnected young man. Her death is just what he needs to overcome his inhibitions and learn that life is about caring for those around you. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl does avoid a direct romance between Greg and Rachel, but just barely.

Me and Earl and the Dying Girl is worth a watch for the visuals and the performances, but could have been even stronger had the source material given more agency to Rachel and the film’s resolution not been so clear and clean.

Check out my review of the film on KCTV5. (Television review links are usually active for a month after the air date)

Comments on this entry are closed.