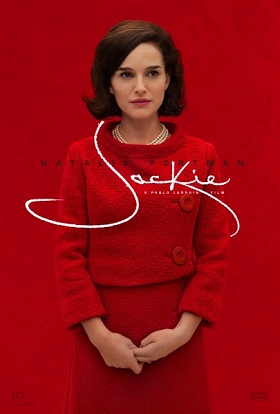

Director by Pablo Larrain opens his film, Jackie, with his title character walking alone along the beach in New England. A beautiful strings arrangement is all that accompanies Jackie Kennedy (Natalie Portman) as she stares resolutely into the chilly breeze, and even on this gusty expanse of the waterfront, the woman looks perfectly assembled: the model of grace and beauty. Yet as the score hints at, nothing is at all right, and what began as a gentle and majestic string adagio turns sharp and ugly in an instant. As the movie unfolds from here, this seems altogether appropriate, for the picture is called Jackie, and it is a snapshot of a life that appears majestic and gorgeous at first, only to devolve into a tragic opera of confusion, trauma, and pain.

Larrain arranges his film around three different interviews with Jackie Kennedy to draw out the story that he wants to tell, one primarily concerned with J.F.K.’s assassination. Chronologically, Larrain starts at the end of his timeline, during a day-long conversation Jackie has with a reporter (Billy Crudup) who’s looking to get the first public interview with the first lady after her husband’s murder. Set a week after Dallas, once the state funeral had concluded and Jackie was secluded in Hyannis Port, Mrs. Kennedy speaks frankly, albeit occasionally off the record, about her time as first lady.

The movie uses this conversation to springboard back into a flashback of a different interview, one that took place on television when Jackie gave her famous primetime tour of the White House in 1962. Far more guarded and produced, this interview was the one most Americans remember, as it showed Jackie in her element as the consummate hostess and conservationist. A notorious antique hound, Jackie spent much of her time in the White House scouring the country for original White House artifacts in an attempt to instill a sense of legacy and history into the Executive Mansion. Yet Jackie doesn’t linger in this timeline very long, and jumps again to a different interview just days after the assassination, one with a priest (John Hurt) with whom Jackie is the most honest about her feelings.

As the film dances between these interviews, brief glimpses of the day that binds them all together come in increasingly longer chunks, circling the drain of November 22nd, 1963 with a dreadful inevitability. The structure of the film seems a bit random at first, yet as things progress, the deliberate nature of the set-up comes into focus. At its core, this is a film about history and legacy, about Jackie, Bobby Kennedy (Peter Sarsgaard), the U.S., and even the world at large coming to grips with the loss of John F. Kennedy. The president for not even three full years, the murder of J.F.K. meant that people had to quickly reconcile what the man’s brief time in office meant within the context of the United States’ history as a whole. Each of Jackie’s three interviews deals with the construction of this legacy, and how the key players in J.F.K.’s life fit into it before and after his death.

The film presents the immediate hours after the assassination as chaotic and terrifying. Frazzled, in shock, and covered head-to-toe in her husband’s blood, Jackie flies on Air Force One with Lyndon Johnson (John Carroll Lynch) and the presidential detail as they scramble to keep the country on its feet. Although her performance throughout the picture is nothing short of a revelation, these are Portman’s strongest scenes, as they are played with an acrobat’s care: balancing deftly between confusion, resolve, and despair. Just a handful of hours removed from her husband’s head exploding in the car seat beside her, Jackie is already planning her husband’s funeral and talking absently about arrangements that need to be made.

Bobby Kennedy takes charge once the group is back in Washington, and makes it clear to everyone, including the new president, that Jackie is going to get whatever she wants. Keenly aware of how fragile a state both Jackie and the country are in, Bobby wants to make sure the image of the Kennedys, and the notion of what they represent, is as well preserved as the memory of the slain president himself. Ultimately, Bobby has little to worry about, for Jackie treats the funeral arrangements with a deadly seriousness that speaks to the larger “legacy” theme of the picture. Just like the furniture Jackie had been so keen to preserve in the White House, how the funeral proceeds ties into a larger narrative about the country and her family’s place in it.

Yet this isn’t a puff piece. As Jackie’s conversation with the priest illuminates, part of what drives Jackie and Bobby is a sense of pride and vanity. Indeed, who these people are only mean something as it relates to the history of the man who just died. How Bobby and Jackie will be remembered and written about relies nearly as much on how the country reacts to J.F.K.’s death as to what that man accomplished while president. Thus, Jackie is most interesting when it pulls the curtain back on Bobby and Jackie’s insecurities, and their attempts to overcome them via the bolstering of the fallen president’s legacy.

Those looking for an inside peak into the married life of Jack and Jackie, with whispers of Marilyn, pill-popping, family intrigue, or the like will be sorely disappointed. These elements are hinted at yet never explored, and the picture is better for it. Jackie is the story of one woman’s attempt to put the pieces of her life back together following an unspeakable tragedy, and what that means when one is doing it on the biggest, most public of stages. Besides being gorgeous to look at (director of photography Stephane Fontaine does amazing work), the film is a fascinating exploration of an American tragedy through the eyes of a woman many recognized but didn’t know. It is a story that starts off with untold promise, only to veer off ever so slightly into the grotesque, like a string arrangement that starts out gorgeous only to veer off-key.

Comments on this entry are closed.