[Rating: Rock Fist Way Down]

In theaters and on digital and on demand on February 25.

Watching Big Gold Brick is like watching a toddler turned loose in a room full of their favorite toys. It’s good natured but it is still chaos, with everything that has ever brought the kid any enjoyment hauled out and thrown across the space in a blind, hyper explosion of enthusiasm. The child has no real concept of how to play with a train, a blanket, a paintbrush, and a Star Wars Lego set all at once, but a free pass to have fun has been granted, and they aren’t going to leave a single item untouched.

Writer/director Brian Petsos grabs at anything he can get his hands on when attempting to cobble together a coherent narrative in Big Gold Brick, borrowing from several different genres and narrative techniques: the result much like the aforementioned toddler’s dilemma. The tools to have a good time are there, sure, but in an attempt to enjoy it at all, the film drowns in an avalanche of its own making, suffocating inside a room clogged with disparate toys that don’t make any sense together.

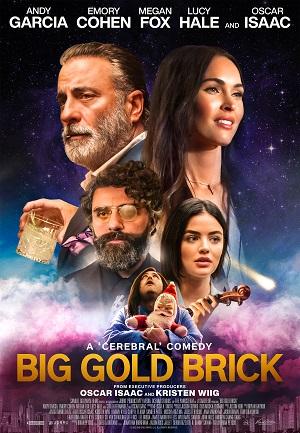

The story is told in flashback via narration by the movie’s central character, writer Samuel Liston (Emory Cohen), who is on a publicity tour of sorts for his new book. Samuel’s story begins with a drunken binge some months earlier that brought him and Floyd Deveraux (Andy Garcia) together by chance, with the latter hitting the former with his car. Hoping to make amends, Floyd offers to put Samuel up as a guest in his home while Samuel recuperates and works under exclusive contract as Floyd’s biographer.

Samuel’s telling of the story and the flashbacks don’t always align, however, painting him as an unreliable narrator in a story that already has its fair share of head-scratchers. Alternating between creepy, disconcerting, funny, and scary, Petsos and his script keep the audience off-balance throughout the first two acts, which to the film’s credit, seems entirely the point. Yet when Petsos throws the kitchen sink into the movie’s fuel tank, including a possible haunted house scenario, intrigue about Floyd’s mysterious past, hallucinations, seductions, and a half-assed attempt to turn the Devereaux family into a twisted Wes Anderson-lite coterie of kooks, the wheels come off Big Gold Brick.

Unfortunately, that catastrophic narrative failure occurs only 45 minutes into this thing, leaving a near-unbearable 85 minutes of nonsensical filmmaking to get through to make the finish line. Megan Fox, who plays Floyd’s philandering 2nd wife, seems to exist in the story for no other reason than to get her into skimpy negligée, which amazingly still gives her more to do than Lucy Hale and Leonidas Castrounis, who play Floyd’s “edgy” children. Oscar Isaac pops into the third act to add another quirky note to what is an already cacophonous narrative, and while mildly amusing, he only further frays the strands of a story that has too many loose ends.

The combination of erratic score selections, Samuel’s fragile mental state, and the frantic editing indicate that the jagged storytelling is a part of a larger thematic tapestry meant to evoke a connection between Samuel and the audience. And while not a particularly good time, all of this might have been interesting if Samuel or his story were in any way sympathetic or relatable, which they just are not. Like the abrasive score, which seems to delight in juxtaposing mood and tempo, Samuel and this world he opens up for the audience is uncomfortable, unappealing, and untrustworthy. If the best movie characters seduce the viewer, enticing one to spend time with them and the world they inhabit, then the worst are like Samuel, Floyd, et al: unreliable, unsympathetic, uninteresting hucksters who lack not just a good story, but the faculty to tell it well.

Andy Garcia seems to be having fun with it all and is by far the most compelling morsel of a story that can’t seems to settle on just one or two interesting hooks. Cohen is the lead, though, and must carry all of this while playing Samuel as drunk, deluded, scared, composed, empowered, and terrified from scene to scene: the flashbacks mixing it all together with all the control and consistency of a bouncing roulette ball. It doesn’t serve the narrative (or the actor) well, both of which suffer from the script’s schizophrenic tendencies and inability to settle on a broader tone.

Mixing Wes Anderson character quirks with a Knives Out undercarriage inside a Bonfire of the Vanities narrative structure, Big Gold Brick and Petsos seem to know what they want in the broadest sense, yet get lost in a tangle of ideas and personalities en route. An unsympathetic, emotionally frantic lead and about six too many subplots crater a story that is already running on fumes and can’t seem to find its bearings despite 132 minutes of effort. There are some interesting moments and broader ideas (like the fact that everyone seems to know about Samuel’s book without having read it), yet like the eponymous title, they are all sparkle without nourishment: a big, fat chunk of something that seems valuable at first glance, but is too cumbersome and unwieldy to enjoy in its present state.

Comments on this entry are closed.