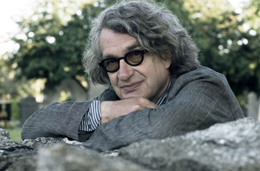

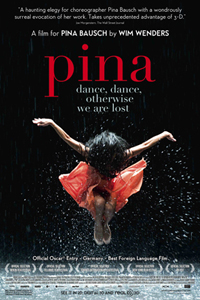

I don’t get a lot of opportunities to interview filmmakers, so when I got an email last week telling me that Wim Wenders was available for phone interviews, I sort of exploded. Not just because of his new 3D dance film, Pina, which has been rightfully nominated for the Best Documentary Oscar, but because I rank his 1984 master-heartbreaker picture Paris, Texas among my all-time favorites.

I don’t get a lot of opportunities to interview filmmakers, so when I got an email last week telling me that Wim Wenders was available for phone interviews, I sort of exploded. Not just because of his new 3D dance film, Pina, which has been rightfully nominated for the Best Documentary Oscar, but because I rank his 1984 master-heartbreaker picture Paris, Texas among my all-time favorites.

We only had 15 minutes, so I stuck mostly to his current film. Read on for his thoughts on 3D, how to fit one art form into another, and the documentary format:

You’ve said that you want to shoot in 3D for the rest of your movies. How does 3D compare to 2D in the production process?

It is very different. Already when you think of your shots, or when you think of the scenes, you have to imagine them differently. You sort of have to walk away from storyboarding, because storyboarding you can only do two-dimensionally. A drawing is a drawing, (if) it’s two-dimensional, you can do whatever you want, (but with 3D), you have to predict the kind of space of scenes.

And then you have to be somewhat more exact because the people in front of the camera are so much more present. They’re so much more there, and (it’s) a huge challenge for actors to be in front of 3D cameras because of the presence, every little bit of overacting immediately becomes gigantic, so you’ve got to be very very careful. If you imagine a two-dimensional stream, a single person is like a cut out, it is a silhouette, and in 3D, you have something very amazing, you have volume, there is a voluptuousness – the body is round and the face is a landscape. And before you know it, you think you really think you could be standing in front of that person.

And then you have to be somewhat more exact because the people in front of the camera are so much more present. They’re so much more there, and (it’s) a huge challenge for actors to be in front of 3D cameras because of the presence, every little bit of overacting immediately becomes gigantic, so you’ve got to be very very careful. If you imagine a two-dimensional stream, a single person is like a cut out, it is a silhouette, and in 3D, you have something very amazing, you have volume, there is a voluptuousness – the body is round and the face is a landscape. And before you know it, you think you really think you could be standing in front of that person.

So it is very very challenging for actors. (And) it is challenging for screenwriters because you have to imagine writing a really differently. Your Cinematographer has to work for the new guy on set, the Stereographer, who is strictly responsible for three-dimensionality of it, in terms architecture of the shots. It takes a little bit longer, maybe 10%, 15% or 20% longer.

Is there any kind of film that you don’t think would be improved with 3D?

I think there are lots of films that are not improved by 3D. There are not very many films that really have control and have shown us what 3D is really good at. We got used to, for a number years, the idea that 3D is a language for action films, and of course for animation it is fantastic. But in movies of real life, it is very much sort of a roller coaster ride, at least that is how we saw it for the first number of years. And we’ve seen 3D as something that is able to show reality, and is sort of a new idea. It is only slowly dawning on us is that 3D is actually a whole language that can do so much more than it was able in the beginning. So it takes a while before we can really tell how to tell stories differently from before.

I think there are lots of films that are not improved by 3D. There are not very many films that really have control and have shown us what 3D is really good at. We got used to, for a number years, the idea that 3D is a language for action films, and of course for animation it is fantastic. But in movies of real life, it is very much sort of a roller coaster ride, at least that is how we saw it for the first number of years. And we’ve seen 3D as something that is able to show reality, and is sort of a new idea. It is only slowly dawning on us is that 3D is actually a whole language that can do so much more than it was able in the beginning. So it takes a while before we can really tell how to tell stories differently from before.

You’ve incorporated other art forms, or elements from art forms, in your films with Pina Bausch obviously, but also with Nick Cave, and Lou Reed, and basing the original idea of Paris, Texas off of some of Sam Shepard’s poetry. Do you consider film to be a synthesis of other mediums, and how essential are other arts to the format?

Well, movies have the uncanny ability to incorporate all the other arts. Not just music, that’s obvious, with writing, that’s obvious, and architecture, maybe not so obvious, and poetry. Movies are the only art form that can involve all the others and embrace all the others. And that is also why films are one of the most popular art forms of the 20th, and now the 21st century.

Well, movies have the uncanny ability to incorporate all the other arts. Not just music, that’s obvious, with writing, that’s obvious, and architecture, maybe not so obvious, and poetry. Movies are the only art form that can involve all the others and embrace all the others. And that is also why films are one of the most popular art forms of the 20th, and now the 21st century.

In some ways, Pina is more Dance-Theatre than film. How do you appropriate artwork into a foreign medium while doing justice to it?

Well, that was the whole thing – doing justice to Pina’s art. We had talked about this for twenty years, we were friends for twenty-five years, and we talked about it and talked about it. Initially I suggested it seriously, and then she started pushing for me to get to it, and I realized it was not easy. It was actually almost impossible to imagine what my craft and my cameras could do to in order to do justice to what Pina did. And I realized that my craft didn’t have the goods. I was beginning to have doubts that I could do it justice, and I finally admitted to Pina that I did not know how to do it, it escaped me, and I’m afraid I will necessarily have to disappoint you.

Pina sort of understood that, but didn’t lose faith that the two of us could find a way to shoot Dance and pushed me to think harder. Each time we met she would ask “Are you ready now?” and I said “Not yet Pina, I need some more time,” until one day I saw the solution on the movie screen when I saw my first 3D film. It was a concert film, U2 3D, and that answered all the questions I’d ever had on how to film Dance. It was too good to be true, but it seemed that 3D was made to film Dance, and I was also certain that Dance would bring out the best in 3D. It was obvious somehow, it was a really Eureka moment, and from then on I was certain. I told Pina we could do it.

Pina sort of understood that, but didn’t lose faith that the two of us could find a way to shoot Dance and pushed me to think harder. Each time we met she would ask “Are you ready now?” and I said “Not yet Pina, I need some more time,” until one day I saw the solution on the movie screen when I saw my first 3D film. It was a concert film, U2 3D, and that answered all the questions I’d ever had on how to film Dance. It was too good to be true, but it seemed that 3D was made to film Dance, and I was also certain that Dance would bring out the best in 3D. It was obvious somehow, it was a really Eureka moment, and from then on I was certain. I told Pina we could do it.

So once you had that Eureka moment, even once you started filming, you didn’t feel challenged by it at all? It felt like you had it understood?

It was a challenge in many ways because the technology wasn’t quite as far along as I’d hoped. When we shot our very first test, it was funny to see the space and the depth, and it was a disaster to see movement, which 3D was (sometimes) incapable of showing elegantly. My assistant, who was running around in front of the camera, looked like a four-armed Indian goddess, he had multiple legs! It was a serious problem at the beginning of 3D, and it still is if you don’t do it right. Even in a great masterpiece like Avatar, the Na’vi move nicely and elegantly, (but) in the background you see lots of four-armed goddesses.

With 3D, dance and movement is still a critical thing. Eventually we solved it, but it took us two years of testing, shooting and working really hard, and it wasn’t easy. We had to make our own mistakes which, of course, is a bloody privilege. It’s fantastic, if you have no other way to learn, than to learn from your own mistakes. I couldn’t call anybody to give me advice – I didn’t have James Cameron’s phone number. We had shot the bulk of Pina before we even saw Avatar.

With 3D, dance and movement is still a critical thing. Eventually we solved it, but it took us two years of testing, shooting and working really hard, and it wasn’t easy. We had to make our own mistakes which, of course, is a bloody privilege. It’s fantastic, if you have no other way to learn, than to learn from your own mistakes. I couldn’t call anybody to give me advice – I didn’t have James Cameron’s phone number. We had shot the bulk of Pina before we even saw Avatar.

But I was still grateful to Avatar, because at least from then on people could take us seriously. Before when I told people it was Dance-Theatre in 3D, everybody just did “Uh huh, really? Can we see this normally? Please?” But then, after Avatar, we looked more respectable.

A lot of your films have crossed borders – whether it’s a matter of where the financing came from, or subject matter. Even what few words are in Pina are in several languages. Is there a larger importance that Internationality holds for you?

Pina, especially, was about the fact that this is a universal language and her dances are from all over the place. Actually, the company speaks eighteen different languages. If ever I made a film that really had no boundaries, and no national boundaries it has been Pina, because that language belongs to mankind, and not to any race, gender, or nationality.

Pina, especially, was about the fact that this is a universal language and her dances are from all over the place. Actually, the company speaks eighteen different languages. If ever I made a film that really had no boundaries, and no national boundaries it has been Pina, because that language belongs to mankind, and not to any race, gender, or nationality.

Few docs are as artful as Pina, in my opinion. Is it difficult to figure out how to balance the roles of artist and journalist when you’re shooting a documentary?

I think human creativity is one of the greatest adventures on this planet, and to see somebody who invented something, who really invented a new art form, and grasp and translate that to film is as much an adventure as following somebody to the North Pole, or doing research on something. Getting involved with the act of creativity is one of the great adventures. (Pina) is not a journalistic approach, it’s much more of a poetic approach. But I think that is one of the capacities of documentary, to find the essence of something and be truthful to it, and try to bring out its beauty as good as you can, and that’s one possible aspect of documentary.

Another one, of course, is the search for truth which also is excellent. It was strange that in Pina, what we had in front of a camera was in itself fiction. The choreography was fiction. But then again, our entire attitude to it and approach and truthfulness was of course of documentary. It is a documentary film about a fictional context which is, maybe, sort of adventurous.

Comments on this entry are closed.