[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

“This is a story about an obsession,” a title card reads as the documentary opens. Directed by Al Pacino, the documentary feature Wilde Salomé is indeed a meditation on obsession, both in its subject, but also by way of the form of artistic expression itself. Art seems so effortless when done well, like the fabled transposing of notes onto the page via Mozart’s pen, yet any artist, be it a filmmaker, poet, or sculptor, will tell you that art is hard goddamned work. Indeed, for every great movie, painting, or novel, millions of discarded or failed attempts lay by the roadside: the struggle to capture inspiration lost like a child trying to catch a bubble.

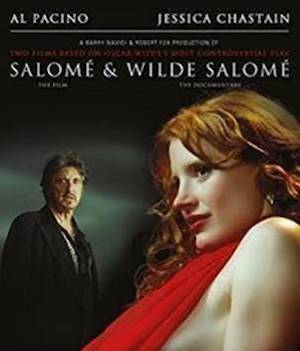

Wilde Salomé follows Pacino’s attempt to stage a theatrical production of Oscar Wilde’s play, ‘Salomé’ in 2006 while simultaneously producing a cinematic version. Pacino’s theatrical ‘Salomé’ is avant garde in style, and is staged more as a reading than a play, with minimalist set design and modern “costumes.” The movie component isn’t just an attempt to film the stage production, however, but rather to bring a similar yet distinct version to life on-screen. In Wilde Salomé, Pacino’s stage and film producers clash over resources and the wisdom of this daunting endeavor while Pacino attempts to peel back the thematic and historical layers surrounding Wilde’s work.

Pacino explains that ‘Salomé’ was Wilde’s attempt to exorcise the emotional turmoil stirring inside of him at the time of its composition, for the play is about the awakening of a passion within its lead. ‘Salomé’ tells the story of King Herod and John the Baptist, the latter of whom lost his head when Herod promised his step-daughter, Salomé (Jessica Chastain), anything she desired in a fit of ecstatic bliss. The character of Salome, like Wilde, came to realize that there was a passion inside that had previously been untapped, and when exposed, could not be bottled back up again. This is indeed a fascinating interpretation of the piece, and adds a layer to the drama that Pacino explores by going to Ireland and England to visit Wilde’s old haunts.

This isn’t just a vanity tour, however. Pacino is interested in speaking to distant relatives, historians, and literary scholars to get a better idea of what Wilde went through as he approached the most difficult period of his life (his indecency trial, and subsequent imprisonment). Gore Vidal, Tony Kushner, Tom Stoppard, and Bono pop up to provide some insight into Wilde as well, and their voices lend some welcome perspective. Oscar wasn’t just an author, but a social critic and socialist who rattled the cages of London’s late-19th century Victorian elite. It’s clear from the documentary that Pacino is fascinated with Wilde and his play, connecting both to the larger story of Wilde as not just a literary pioneer, but a social activist as well.

This isn’t just a vanity tour, however. Pacino is interested in speaking to distant relatives, historians, and literary scholars to get a better idea of what Wilde went through as he approached the most difficult period of his life (his indecency trial, and subsequent imprisonment). Gore Vidal, Tony Kushner, Tom Stoppard, and Bono pop up to provide some insight into Wilde as well, and their voices lend some welcome perspective. Oscar wasn’t just an author, but a social critic and socialist who rattled the cages of London’s late-19th century Victorian elite. It’s clear from the documentary that Pacino is fascinated with Wilde and his play, connecting both to the larger story of Wilde as not just a literary pioneer, but a social activist as well.

It’s all a bit unfocused, though: a little muddled. Throughout the documentary, Pacino shifts from play rehearsals, to reenactments of Wilde’s life, to clips of the film version of the play, to behind the scenes footage of shooting that movie, to real life social events where all these realities merge. Jessica Chastain remarks at one point that she thought she was going to a dinner party, “as Jessica,” but Pacino has instead decided to make it a method exercise in exploring the character of Salome. All of these ideas are interesting, yet as presented, it feels a little too much like Pacino is throwing every idea he has at the wall to see what sticks.

Curiously, despite the fact that he’s in nearly every scene, what’s missing here is Pacino. Although he is guiding the audience through all of this, there seems to be a reluctance to delve into Pacino’s life as an examined counterpoint to Wilde. After all, this is an actor who has enjoyed the pinnacle of success (Godfather) and the depths of critical failure (Gigli). Pacino has never married, but has three kids and a slew of ex’s (famous and otherwise) that speak to an interesting life lived unconventionally. How Wilde inspires Pacino as a person is never really explored within the context of the latter’s life, and it is an aching, unspoken wound that Wilde Salomé never addresses.

As the documentary moves into its third act, and the middling reviews start coming in for Pacino’s “reading” of ‘Salomé’, one gets the sense that the documentary is going in the wrong direction. Pacino’s interpretation of the material not as a play, but as an avant garde reading rubs some critics and audience members the wrong way. There’s a raw, brave honesty Pacino offers up in his documentary that shows just how disappointed the man is in his vision not connecting with audiences, and these silent moments are some of the best of the documentary.

As the documentary moves into its third act, and the middling reviews start coming in for Pacino’s “reading” of ‘Salomé’, one gets the sense that the documentary is going in the wrong direction. Pacino’s interpretation of the material not as a play, but as an avant garde reading rubs some critics and audience members the wrong way. There’s a raw, brave honesty Pacino offers up in his documentary that shows just how disappointed the man is in his vision not connecting with audiences, and these silent moments are some of the best of the documentary.

“He was expressing his own destiny in this play,” Pacino says, captivated in reflection. Indeed, the more interesting story here is one artist’s personal connection to a piece of theater, and how he isn’t able to translate that love into his own unique expression. Like so many actors, writers, songwriters, or poets who feel a bolt of inspiration hit them, Pacino’s struggle reflects the difficult-to-grasp reality of art. Just because you see it in your mind, and feel it in your heart doesn’t mean you can easily express it in a way digestible to others. Art is difficult, and for every success, there are hundreds of failures. It’s striking that even for an actor/director as talented as Pacino, inspiration and passion don’t always equal success: the destiny of Pacino seems permanently separated from ‘Salomé’ to his bitter dismay.

Again, had the documentary delved into this a bit more, and asked Pacino to reflect on other instances where he experienced this, there might have been something truly special to explore. As it stands, Wilde Salomé is still a fascinating exploration of art as presented by a true artist, and is brave enough to dwell on its failure. Were this documentary more about that than the exploration of ‘Salomé’ it might click more than it does. Opening in limited release today, it’s worth seeing if only to watch a true artist try and fail: a rare thing to get a look at from as intimate a perspective as what Pacino offers up here.

Comments on this entry are closed.