2017 Cannes Palme d’Or winner The Square, opening today at the Tivoli, is a lot of things: a biting satire, a class warfare fable, a head-scratcher featuring a chimp wearing lipstick.

The film, written and directed by Ruben Östlund, follows one man’s dizzying drama over the course of a few weeks, and weaves in multiple themes ranging from a modern bourgeois disconnect to personal segmentation, touching on a lot but never settling on any message or truth. And while this might not matter for some films, which seek only to hold up a mirror to the audience, The Square is trying for something grand, here, and doesn’t quite pull it off.

At the center of all this muddled messaging is Christian (Claes Bang), the chief curator of a modern and contemporary art museum in Stockholm. The model of a disconnected, middle-class snob-in-training rubbing elbows with the art community’s rich and famous, Christian dresses the part of an influential opinion-maker with his red-rimmed glasses, tailored suits, and obligatory Tesla. Christian wants a big, viral-like moment for his museum and its new exhibit, a notion which is itself a paradox since the stodgy, old-money regulars of the art world aren’t exactly plugged into the Facebook universe of ice bucket challenges, etc.

This new exhibit, the eponymous “square,” is a physical safe space that’s supposed to be a “sanctuary of trust” where people act as members of a compassionate community adhering to the Golden Rule. It is meant to start a larger conversation about poverty, classism, generosity, and awareness, and so to build the desired buzz, Christian brings in a couple of millennials to craft a dynamic marketing campaign.

In the first of multiple moments of in-your-face irony, Christian is waylaid by a subplot about thieves stealing his phone and wallet, which leads to an ill-advised revenge scheme that puts Christian in way over his head. Another involves a random hook-up between Christian and an American journalist, Anne (Elisabeth Moss), who doesn’t appreciate the fleeting nature of their intimate connection. Yet another centers on Christian’s two daughters, who he struggles to connect with and set a good example for, despite his own failings and best intentions.

It all seems to drive home this point that despite humanity’s advanced evolution, despite the reflexive awareness that allows us to create knowing artistic pieces like the “square,” that people are rarely more than cowardly, reactionary creatures. Were it not for a few scattered, conscientious members of the herd (like the boy who doggedly pursues Christian for falsely accusing him of theft, or a press conference attendee who defends a man with Tourette’s), mankind would retain little more dignity than the apes and chimps locked in our zoos.

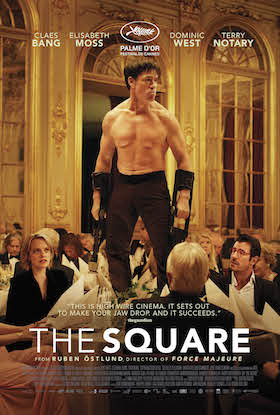

In The Square’s climactic, tedious third act set-piece, this too is hammered home with all the nuance and subtlety of a jackhammer. With all the museum’s wealthiest donors and patrons in attendance for a black-tie dinner party to celebrate the opening of the square exhibit, a performance artist barrels into the banquet hall as a fully invested and committed ape-man. Aggressive, forceful, and brutish in all the ways a wild animal can be, this artist takes things too far, and like the beggars on the streets outside (which appear conspicuously throughout the film), the wealthy onlookers cast their glances away: hoping the ugly sight will vanish if not acknowledged.

Again, it is all a little too on-the-nose. At 150 minutes, the thematic tissue connecting the art exhibit’s notions of community and reciprocity with Christian and his world’s disregard for the society that surrounds them is established by the end of the first act. Östlund’s stubborn refusal to trim his scenes, or to excise redundant plot-lines that dance around the edges of the larger story without contributing anything new only serve to pad the effort out unnecessarily. This is a shame, too, because there’s some great humor to be mined in a lot of these scenes, and in a tighter script, some of it might have been put to good use.

Claes Bang does a fine job conveying the frazzled state of a man beset on all sides by a carefully manicured life exploding all around him. Indeed, in his attempt to create a viral moment for the museum, an explosion is just what he gets, much to his humorous dismay. Dominic West appears in a few scenes in what amounts to a glorified cameo, as does mo-cap expert Terry Notary as the dinner party performance artist, Oleg. There’s a reason Notary is front and center on most of the advertising for The Square: his work is electric, and he just about steals the movie in a little over five minutes of screen-time.

Östlund has reached down deep to try and tell a story that hits on a number of different themes connected to community responsibility, social awareness, and the importance of understanding. The Square takes place in a world where the walls between the haves and the have-nots aren’t just thick and tall, but set into a foundation not easily shaken. The series of unfortunate events that strike Christian in rapid succession threaten to do just that, and as a man with one foot in the door of high society, these calamities rush through the breach and infect everyone on the other side. It is an interesting thing to behold, if only mildly entertaining and occasionally tedious.

Comments on this entry are closed.