The Revenant is a hard film to write about.

In a year of quiet, dull, grey and unassuming films, this film is like a firecracker being released into a crowded room. It’s as if whilst standing in the bank, one of the fellow patrons decided to kill the person in front of them and eat the marrow from their bones. It’s as if a teacher, mid-lecture, stripped naked, pulled a pool noodle out of their desk and ran out of the building screaming at the top of their lungs, hitting students with the noodle all the way. It’s striking.

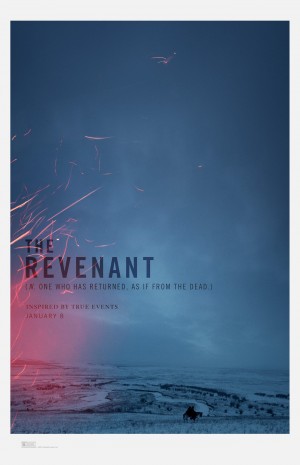

This film has probably been the most hyped art project of the year, Star Wars for the glasses-wearing, Lynch-watching, chai-drinking crowd. The combo of Birdman helmer Alejandro G. Iñarritu, professional Oscar loser Leonardo DiCaprio, and the Hearts of Darkness-worthy levels of production insanity have made critics and audiences salivate at the mere concept. Add a fantastic trailer, and suddenly you’ve got an art hit. Everyone is clamoring to see this thing. My mother wants to see this thing. It’d be extremely difficult for a film with so much hype to live up to everyone’s expectations.

So how does it actually do?

Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo is one of the most infamous productions in the history of the cinema.

Filmed over fifty miles away from civilization, utilizing real natives from deep in the Bolivian Amazon as well as a massive crew forced to hunt their own food and tug a real ship up the side of a mountain, the film has acted as a testament to the hubris and ambition of one of cinema’s most daring artists. The film is a masterpiece, with beautiful yet horrifying cinematography and a deeply troubling and utterly fascinating leading performance from the great Klaus Kinski. It also has one of the worst endings in cinematic history. Despite the film’s greatness, it showcases a deep and obvious flaw.

Filmed over fifty miles away from civilization, utilizing real natives from deep in the Bolivian Amazon as well as a massive crew forced to hunt their own food and tug a real ship up the side of a mountain, the film has acted as a testament to the hubris and ambition of one of cinema’s most daring artists. The film is a masterpiece, with beautiful yet horrifying cinematography and a deeply troubling and utterly fascinating leading performance from the great Klaus Kinski. It also has one of the worst endings in cinematic history. Despite the film’s greatness, it showcases a deep and obvious flaw.

Whether or not you are willing to consider Fitzcarraldo a great film should help determine whether or not you’d be able to consider The Revenant a great film. Many are not.

I am.

The Revenant, based on the tall tale of Hugh Glass’ epic journey to take revenge on the man who left him for dead after he was mauled by a bear, is a flabby, ambitious mess that may well be one of the most endlessly fascinating films of the year. The sheer fact this thing exists is incredible. There are things that were done and happen onscreen that, for reasons of the safety and mental stability of everyone involved in the making, should just not have happened.

The film is insane. It’s hubris incarnate. It’s a madman pulling people into the wilderness and putting a camera on the ensuing chaos. It’s a master filmmaker so high on his own blinding confidence that he demands every second be treated with the raw, terrible splendor of a war film. It’s a film so committed to its own plans of greatness that it draws out the already infamous bear mauling for a brutal seven minutes of screentime.

The film is insane. It’s hubris incarnate. It’s a madman pulling people into the wilderness and putting a camera on the ensuing chaos. It’s a master filmmaker so high on his own blinding confidence that he demands every second be treated with the raw, terrible splendor of a war film. It’s a film so committed to its own plans of greatness that it draws out the already infamous bear mauling for a brutal seven minutes of screentime.

Perhaps I should slow down. I’ve been getting rather excited about this thing. 2015 has been an exceptionally underwhelming year, film wise, with almost everything with money behind it being wrote and uninteresting, and the fringe work being half-baked and amateurish. There have been several highlights (among them George Miller’s return to Mad Max, the news procedural Spotlight, the beautiful and delicate Carol) but there quite simply hasn’t been anything working on this level of sheer ambition. Few films have been made on that level.

I don’t just mean recently either, I mean few films period. People don’t spend this much money and put themselves in this much danger for cerebral art flicks. Kubrick did this, as did Tarkovsky. The aforementioned Werner Herzog did this, and his epic struggle can be seen in the brilliant documentary Burden of Dreams. For me, the best comparison might actually be the truly insane Czeck production Marketa Lazarova, directed by František Vláčil, that completely recreated a functioning Medieval Bohemian encampment so that the cast and crew could reach further into the time and into the material.

The Revenant is but one more rare, glorious example of this ridiculous scale of filmmaking. The stories of the production are already becoming famous, with major crew injuries and tales of Leo sleeping in animal corpses (a scene that, thank god, survives in the final cut). The film, too, has garnered a lot of attention for being shot entirely with natural light. If I were Chivo (Emmanuel Lubeski, the film’s rapidly becoming canonical cinematographer), I would actually be insulted that natural light has been the focus of the visual discussions of the film.

The Revenant is but one more rare, glorious example of this ridiculous scale of filmmaking. The stories of the production are already becoming famous, with major crew injuries and tales of Leo sleeping in animal corpses (a scene that, thank god, survives in the final cut). The film, too, has garnered a lot of attention for being shot entirely with natural light. If I were Chivo (Emmanuel Lubeski, the film’s rapidly becoming canonical cinematographer), I would actually be insulted that natural light has been the focus of the visual discussions of the film.

Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon is sometimes called a film that does not appear to have been filmed, it is painted by one of the great masters of the era the film evokes. Something similar can be said for The Revenant. Save for a few examples of fogging, you forget the camera in this film. You’re in the mud, wading through water and snow and dirt. You’re sinking into the Earth. At times you feel as though you are stuck in the wet ground along with the characters. You can practically smell the dried blood. The harshness of the production is not apparent in Chivo’s cinematography, it is so fluid and natural you forget it is there, but it is wildly apparent in the images it creates. The lives of the characters are harsh, terrible, dirty and painful.

The film does not merely depict its era but submerges you into it. It’s more than costumes and some language ticks. The psychology of the cast is fundamentally different. The world looks different. People react to their world with a far more adversarial disposition. The wild is not some wild yonder ready to be conquered. It is not waiting for civilization. It’s a dangerous place, where we are still subjects of the food chain and the elements. Many early critics have compared the film to Terrence Malick but that’s entirely wrong. Malick went out into the wild and found the wonders of the Divine. Iñarritu did the same, and found a world ruled by Darwin and Neitzche. The world is uncaring, and even the supernatural may only exist to drive further human savagery. To survive, one must abandon their more human element.

DiCaprio shows this spectacularly. His performance is something to behold, delivered mostly through grunts, heaving, gasps and broken body language. If it were not for his current position in pop culture, I’d claim the performance is too bizarre for Oscar gold. I’d be shocked if he has a hundred lines of dialogue in the entire film. His makeup, too, is marvelous. Scarring that looks not just real but actively painful. Seeping, stretching, tearing, rotting.

DiCaprio shows this spectacularly. His performance is something to behold, delivered mostly through grunts, heaving, gasps and broken body language. If it were not for his current position in pop culture, I’d claim the performance is too bizarre for Oscar gold. I’d be shocked if he has a hundred lines of dialogue in the entire film. His makeup, too, is marvelous. Scarring that looks not just real but actively painful. Seeping, stretching, tearing, rotting.

However, with so much attention paid to DiCaprio, many reviews have been shafting Tom Hardy’s equally important role, which for me dominates this film. Hardy’s signature mumbling has never been more meaningful or fascinating. Tom Hardy is not in this movie. Hardy is replaced by a coyote. John Fitzgerald, with his extremely thick Southern accent and scalping scar, looks through the characters around him. He’s been turned into a creature of instinct. He does not act with malice or anger as much as a need for survival. He is a man shaped by the horrors of warring and the frontier. This is a common theme for the film.

I could keep going for a while. I could talk about the film’s spectacular action sequences, as riveting as any from the best blockbuster. I could talk about the clever way it brings the film’s conflicts into a social context, still relevant today, by tying it into the struggles of the Arikara Native Americans in the area. I could talk about the beautiful and invisible use of CGI. I could talk about the film’s fabulous editing, costume design, sets, props, makeup, supporting cast, sound design and score. I could talk about how its sense of magical realism at times ties the film directly into the rest of Iñarritu’s oeuvre (look for a comet).

The film is not perfect. Far from it. It becomes repetitive near the end of the second act, the few instances of ADR are obvious, and the aforementioned magical realism can, at times, make it unclear as to what Iñarritu is trying to say. This last point in particular can be a sticking point for some, as it never really explains whether or not the more artful moments of the film are meant to be hallucination or artful hat-tip towards a metaphorical meaning for the entire piece. The film often begs for a second edit, or shows just how the hubris of a director can detract just as much as it can add to a film. Well, not as much.

The film is not perfect. Far from it. It becomes repetitive near the end of the second act, the few instances of ADR are obvious, and the aforementioned magical realism can, at times, make it unclear as to what Iñarritu is trying to say. This last point in particular can be a sticking point for some, as it never really explains whether or not the more artful moments of the film are meant to be hallucination or artful hat-tip towards a metaphorical meaning for the entire piece. The film often begs for a second edit, or shows just how the hubris of a director can detract just as much as it can add to a film. Well, not as much.

Fitzcarraldo is essential watching. It’s a work of striking beauty and deep-rooted obsession. Despite its major shortcomings, the film is quite simply too much of an event and artistic achievement to be ignored. Herzog’s work is a flawed masterpiece, perhaps not his best but still miles beyond most films that are made.

The Revenant is the exact same. It’s a flabby, beautiful, horrifying and spectacular oddity that skyrockets beyond its competition. It’s over-ambitious. It’s pretentious. It’s flawed. None of that matters. This is not an example of good ideas going to waste due to a flawed manufacture, we are talking about smudge marks on a painting the size of a building. When you’re talking about a film that so successfully reaches the physical and ethereal heights it attempts, who cares if it stumbles a bit on its way. When you’re strapped to a rocket, spiraling you around the planet, there will be some turbulence.

Even if you can’t get over those flaws it’s more than worth your time. I urge everyone who reads this, GIVE THIS THING MONEY. Tell studios that this kind of film is worth it. Tell the powers that be that unique and bizarre films, driven by utterly singular artists are worth the money it takes to produce these absolutely insane works. We need more of these. We need more people like Iñarritu working on budgets like this.

The Revenant is one of the most ambitious films in recent memory and one of the best pictures of the year. Go see it. It’s worth your time and money.

{ 1 comment }

I have wanted to see this movie based solely on the previews. Now: I MUST SEE THIS!!!!!!!

Comments on this entry are closed.