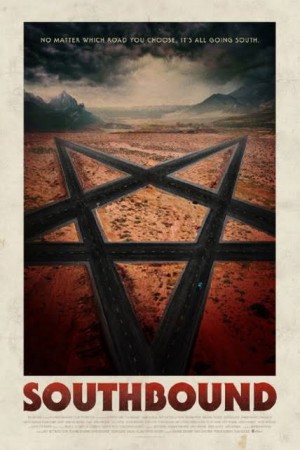

Southbound is a multi-director horror anthology that explores the consequences of seemingly unforgivable actions by its principal characters. The film is a grim series of vignettes that show its subjects hurling into a dark void as a result of the betrayals and selfish actions that led them into its purgatory, which is represented by its desert landscape setting. The film has no preachy message about the nature of forgiveness. With the exception of a cheating middle-aged man who appears halfway through Southbound, most of the characters are irredeemable. The film derives its hard edge from the notion that people who cannot face their misdeeds deserve to be cast off into hellish places of their making.

The Southwestern desert is shown as a kind of hell that the characters drift through and will never escape. There is nothing original about the use of harsh desert landscapes and desolate highways as stand-ins for nether worlds and purgatory-like settings. The feelings of dread, suspense and horror are carried over fluidly from one segment to another by each director. The director of each segment consistently conveys the characters’ desperate, futile attempt at escaping their horrible deeds while keeping the film visually consistent.

Southbound’s well-crafted opening sequence shows two shaken, bloody men (Matt Bettinelli-Opin and Chad Villela) barreling down a highway in an old pick-up truck, pursued by black, skeletal, CGI-created ghouls that resemble the grim reaper. The two men, whose reasons for running are not immediately clear, stop at a gas station where a spaced-out waitress watches Night of the Living Dead on an old television. After a creepy, menacing encounter with the waitress, the men continue. The flying demons remain in pursuit until the two men fall into a kind of loop in which they continually end up at the same truck stop, Each time, the same waitress confronts them, greeting the two fleeing men like the leader of a kind of Purgatory Welcoming Committee. The two men, escaping from a horrible incident that is explained in the final segment of the film, run desperately from their horrible misdeeds, yet remain trapped.

The film’s next segment centers around Sutter (Kristina Pesic), the singer of an all-girl rock band who is haunted by the death of one of her friends and fellow band mates. We become aware that she too wanders through the same hellish landscape that swallowed the two men. This sequence of the film introduces a cryptic occult element that adds to the film’s mystery and other-worldliness that has been established by the warping of the desert landscape. Dark forces work underneath the surface of the film’s setting and actions that are rightfully never explained.

Middle-aged cheater Lucas (Mather Zickel) finds himself driving down the same highway that led the characters from the first two segments into their grim predicaments. Here, we realize that the segments of the film interlock when Sutter wanders into Lucas’ segment of the film, where he must confront the secrets and lies of an affair he is having. The third segment, which is the most gruesome and suspense-filled, presents Lucas with an objective that involves saving another life, albeit in a bloody, squirm-inducing way. This segment seems to present the only notion that the characters can be forgiven for the bad things they’ve done. Lucas struggles hard for redemption in a way that the other characters seem incapable of.

Dale (David Yow) somehow wanders into the film’s netherworld to find his sister, who went missing years ago. The film hints that she murdered their parents, and when Dale finally tracks her down in Southbound‘s world, she is etching occult symbols into the back of another man. But she accepts her fate as a soul cast off into Southbound’s strange landscape. Among characters who try desperately to escape the personal hell that they’ve created for themselves, she is the only person in the film who seems at peace with the place her actions have led her.

And so Southbound avoids becoming a prolonged torture porn, like many modern horror films, by juxtaposing characters who seek redemption, against characters who do terrible things to other people while desperately trying to escape from the path that has led them to their fate. The film circles back to the two men in the pickup truck, who we first assume are innocent victims being pursued by grim reaper-type monsters. But when we see the two men commit an inexplicable violent act near the film’s end, we realize that they too are trapped in the film’s desert-set netherworld because of their misdeeds.

Like many of the other characters in Southbound, they cannot face the horrible things they’ve done. Southbound says more about the cause and effects of horrendous things than similar films, such as the unwatchable ABCs of Death, another horror anthology that presents a series of vignettes containing gruesome images that seem to exist for their own sake. Southbound has more in common with the existential nightmares in some of the greatest Twilight Zone episodes. It’s far from perfect, but Southbound is one of the few horror movies I’ve seen that tries to explore the notion of cause and effect regarding the horrible things that people do to each other.

Comments on this entry are closed.