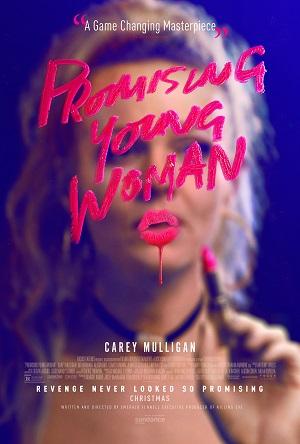

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

Opens Friday December 25 in theaters only

A tale of revenge that is as rooted in 2020 as Les Misérables is to the French Revolution, Promising Young Woman is a no-holds-barred exploration of sexual assault and accountability in a post-#MeToo era, well aware of the present, yet largely foggy on the past. The film follows Cassie (Carey Mulligan) on her quest to bring justice to those that would exploit vulnerable women, and while it has a lot to say about just desserts, it (reasonably) has more questions than answers about how to move forward.

Promising Young Woman opens in a nightclub where a group of businessmen are casually bemoaning the complications of woke culture, transitioning all too easily from there to a targeted debate about a nearby woman “asking for it.” Barely conscious from the looks of it, the woman is seemingly easy prey for one of the men, who talks her into a cab ride back to his place where things turn physical in a hurry. Once the man crosses the line and begins to engage in full-blown sexual assault, the woman comes to, and reveals her drunken stupor to be an act, which terrifies the man like a fly suddenly aware of the spider’s web.

The woman is Cassie, a 30-year-old barista who still lives with her parents and spends her weekends fishing for assholes at bars and clubs so she can spring this trap. Although writer/director Emerald Fennell never shows Cassie completing her “work,” always cutting away after she’s revealed her ruse, a color-coded journal implies that she’s been doing this awhile, and that some men get harsher punishment than others. Cassie’s work isn’t just a hobby, though, but rather a full-time obsession that’s keeping her from moving forward with her life in any meaningful way. Those few people still in her orbit, like her well-meaning boss (Laverne Cox) and parents, all agree that she’s in one hell of a rut.

The reasons behind all of this come in pieces throughout the film, for Cassie wasn’t always like this, and seemed to change for the worse after she dropped out of medical school. Cassie’s chance encounter with a former classmate from that era, Ryan (Bo Burnham), puts her at a crossroads, for he’s at once a seemingly “good” guy willing to guide her out of her funk, but also a connection to the inciting event that put her there. The trips to the clubs and bars to punish predatory vermin have been random up to this point, but Ryan provides Cassie with the opportunity to target those that hurt a med-school friend, whose tragedy inspired the whole revenge crusade.

Without moving into spoiler territory, it should suffice to say that there aren’t any easy answers in Promising Young Woman, and even less optimism. Fennell’s script doesn’t leave much moral wiggle-room for the men in this film, who all seem to think they are good guys despite their place on a sliding scale of douchebaggery. Even Ryan, who possesses some level of self-awareness and reasonable boundaries, can’t help but to blurt out, “What are you doing working here?” to Cassie when he happens upon her working in the coffee shop. He’s better than most because he knows how rude this statement is, yet the film doesn’t afford him or the other men much sympathy (except, perhaps, Cassie’s dad, played by Clancy Brown in a scene-stealing turn).

As Promising Young Woman moves into its third act, it becomes a treatise on that which is socially obvious. Cassie, short for Cassandra, is the name of the Trojan priestess, after all. A tragic figure from Greek mythology whose defining trait was foresight, Cassandra was cursed by the gods, however, for no one believed her prophesies. Cassie, haunted with the knowledge of what really happened to her friend back in med school, yet with no one willing to do anything about it, strikes out against the curse that dogged her classical counterpart to change the script. The film ably sets this crusade up as a righteous one, yet doesn’t give the audience much in the way of a path forward when all is said and done.

Part of this is a function of the narrative, which surrounds Cassie with the absolute dregs of humanity. These men Cassie dupes can’t answer her pointed questions once her drunken charade is abandoned, wincing at queries like, “What do I do for a living? How old am I? What’s my name?” The people from Cassie’s past that she targets are little better, not because they can’t remember things, but because they can and did nothing when it mattered. A stunning, “oh shit” climax gives audiences a fist-pump moment at the end of Promising Young Woman, yet beyond a feeling of isolated justice, there’s not much for one to turn over and consider once the credits roll.

But maybe that’s the point. Arresting Harvey Weinstein didn’t magically solve the problem of sexual and emotional exploitation in Hollywood, so why should one barista on a revenge crusade be any different? This is the story of one woman’s struggle to find inner peace following a tragic and grotesque experience, and it’s nothing less than a rousing success in this regard. Mulligan’s performance, which comes off like a war-weary soldier dead to all emotion mindlessly pursuing the same cruel mission again and again, stacks layers of nuance within the performance. Fennell’s decision to keep her decked out in rainbow colors sets Cassie up as a cloaked bomb, designed to lure in prey easily dazzled by gaudy accoutrement.

Details like this, along with a frightfully intuitive script, inform the larger story well and add definition to characters that keep developing (or revealing themselves for what they really are) right up to the last frame. Sitting squarely on the shoulders of Mulligan, who carries Promising Young Woman through to the finish line with a balanced presentation of steely resolve and wounded vulnerability, the story transcends its base revenge roots in a way that allows it to speak to a very particular moment in time. A moment where it’s finally vogue to believe women, though only up to the point where male fragility and their sense of righteousness isn’t threatened. It might not be the most satisfying watch for some viewers, but it is the movie the world needs right now: comfort levels be damned.

Comments on this entry are closed.