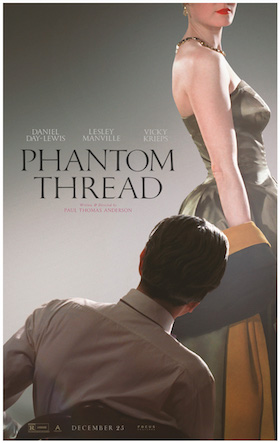

A love story concerned with the intersection of obsession and art, Phantom Thread is a stately drama with rom-com sensibilities. In what the actor claims to be his last role, Daniel Day-Lewis is Reynolds Woodcock, the highest of high-end dressmakers of 1950s London, whose fierce idiosyncrasies fuel his work while keeping most people at arm’s length. Reynolds’ art is everything to him, and like the changing of fashion seasons, people come in and out of his life like the inspirations that fuel his creations: their presence merely fodder for his sketch pads.

The introduction of a young woman into his orbit changes everything for Reynolds, however, and forces him to reevaluate his priorities and what it means to balance his humanity with his art, if indeed they can ever be reconciled. With this arrival of Alma (Vicky Krieps), a hunger stirs in Reynolds (figuratively and literally), and he’s challenged in ways he never has been before and could never have expected to be. Playing referee to all of this is Reynolds’ business partner and sister, Cyril (Lesley Manville), the one consistent human connection the man has maintained throughout his life. It is implied that Cyril has ushered young women in and out of Reynolds’ orbit on several occasions, yet there’s something different about Alma, and the way Reynolds reacts to her, and it sets all three of them on a path towards the unexpected.

Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson’s most recent work has focused on thematic overtones that largely define each picture in broad strokes, using the narrative as more of a buttress. Whether it is a meditation on greed, capitalism, and success (There Will Be Blood), or the nature of interpersonal control vis a vis relationships and the dynamics of social performance (The Master), it is the theme, not the story, that is most important. Phantom Thread is something of a departure in this regard, as the relationship between Reynolds and Alma is as central to the film as the thematic undercurrents. How the two of them grow around the implacable presence of the other, like roots around a sidewalk, represent the backbone of this picture.

It’s an interesting stew, this mix of obsession, love, and art, yet Phantom Thread works because it has an expert craftsman at the center of it all. With three Best Actor Oscars under his belt, calling Daniel Day-Lewis a once in a generation talent seems almost reductive to the point of being absurd. The man stands in a class all his own as a thespian who has ever been able and willing to disappear into his performances. Yet what has always made DDL so mesmerizing to watch has had less to do with the roles themselves, but rather the layers of nuance and complexity he brings to each character.

His Abraham Lincoln showcased an almost otherworldly level of empathy that he seasoned with a tangible sense of emotional and physical exhaustion that manifested in several different outbursts (both big and small). His Daniel Plainview was the picture of unassailable ambition and greed, yet if one looked close enough, his performance in There Will Be Blood allowed for a few cracks in the façade to reveal a tragic void where his humanity seemed to be breaking away, piece by piece. With Daniel Day-Lewis, what one sees on the surface is rarely the full measure of what is actually at play, and if Phantom Thread is indeed the man’s last performance, audiences should take a moment to revel in this magnificence one last time.

When Reynolds winces, sighs, or shudders at the loud scraping of toast, or the presence of butter instead of oil on his vegetables, he communicates volumes. The uncomfortable shifting in a chair, or the subtle passing of a hand near a breast during a dress fitting speaks to a pent-up soul screaming for a release that will never come. Daniel Day-Lewis plays Reynolds as a tortured slave to a series of anxious complexes that have calcified and grown over themselves, and can only be treated with his art and his routines.

Krieps plays Alma with no less intensity, and punches her weight when squaring off against DDL. Her passion is just as potent as Reynolds’, and while the audience doesn’t get much in the way of her backstory, this drive and focus seems to come from the same forge of emotional trauma that fired and hardened Reynolds. At the center of this tug-of-war is Manville, whose Cyril character seems to possess all of the best traits of Reynolds and Alma while retaining none of their worst. After a lifetime of careful observation, she knows where the landmines are buried, and is careful enough to avoid all of them while still retaining an unshakable loyalty to her brother that no one, not even Alma, can break.

Paul Thomas Anderson harnesses these performances into something special here and compliments this on-screen radiance with a careful and deliberate hand behind the camera. The set design speaks to the claustrophobic state of Reynolds’ existence, and the small boxes he puts himself in just to function. Too much room to maneuver or think or feel would be catastrophic for the man, and whether it is the tight staircase leading up to his office, the cozy sports car he drives, or even the low hanging trees lining the streets he motors down in the dead of night, it all has purpose. The colors are likewise largely muted and flat: greens and blues appearing in Reynolds’ world only in the most sedate manner, or when he’s out of his comfort zone.

Phantom Thread oozes purpose with each scrap of its being, and represents some of the best work of Paul Thomas Anderson’s career (and some of the funniest). A story about passion, art, expression, and unshakable obsession, Phantom Thread is also the perfect vehicle for this generation’s best actor to put on a clinic of showing instead of telling. Subtle yet relatable, tender yet funny, and altogether sincere, the film is a tribute to art, artists, and the people they dare to love (along with those who endeavor to love them back).

Comments on this entry are closed.