[Rating: Swiss Fist]

Mr.Jones, out on VOD today, is a movie with all the right pieces and components yet only a passing notion of how to use them to bind its narrative with the hard-hitting themes it is bandying about.

A true story about Stalinist Russia that’s so Orwellian that George Orwell (Joseph Mawle) writing “Animal Farm” is actually incorporated into the script, the film by Polish director Agnieszka Holland looks great and sure does feel important. A movie about the repression of truth by an authoritarian state and one journalist’s quest to uncover a story that could save the lives of millions, Mr. Jones often skates by on this importance osmosis. Indeed, while its exploration of early 20th century fake news may seem prescient, the movie never fully succeeds in its attempt to connect its story and characters to the relevant past and the audience’s present.

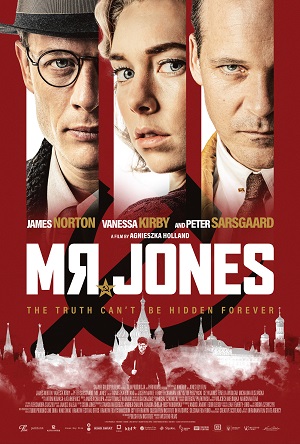

Early on the audience meets Gareth Jones (James Norton), an up-and-coming British reporter who has just come back from Germany with one hell of a scoop. Gareth managed to snag an interview with that country’s new Chancellor, Hitler, yet despite this recent win, the sagging economy has forced his publication to drop him as a correspondent. A fluent speaker of Russian, Gareth hits upon the idea to round out his dictator bingo card by trying to get an interview with Stalin as a freelancer, and sets off for the east to do just that.

The low-level notoriety from his Hitler piece and some press connections get him a travel permit to Russia and an introduction to fellow Brit Walter Duranty (Peter Sarsgaard), the editor of the New York Times’ Moscow bureau. Gareth has a lead on a story about food shortages that are somehow tied to wheat production in Ukraine, along with a well-researched suspicion that the booming Russian economy isn’t what it seems, yet Duranty and the other foreign journalists in Moscow don’t seem to care, or are deliberately not looking. After initiating a friendship with Duranty’s star journalist, Ada Brooks (Vanessa Kirby), Gareth begins to get a picture of what would later come to be known as the Holodomor famine in Ukraine, which he resolves to report on by exploring it himself.

Gareth hustles his way into the Ukraine and then must slip his government handler to get out to see what is really happening in the region, making for one of the best stretches of Mr. Jones. Gareth Jones was a real person whose clandestine trip to Ukraine in 1933 really did blow the lid off of a famine that killed millions as a result of the failed economic and agrarian policies of Stalin’s government. And while the film is most effective when showing Gareth’s horror and shock at what’s going on, it never quite connects the dots of the larger geopolitical mechanics of how this came to pass.

Very little time is spent on how Stalin’s collectivization policies resulted in the famine, which take the wind out of the film’s sails when Gareth is witnessing these effects first-hand. Sure, the audience understands what it is seeing, but they can’t possibly grasp the “why” of it, or how it is connected to Hitler or England in the lead-up to World War II. There’s some quick dialogue early in the film between Duranty and Gareth that hints at an effort to pacify Stalin to keep him on Britain’s side as a check against Hitler, but this isn’t made especially clear to those not already familiar with this history.

It’s not just the broader politics of the world in which Mr. Jones lives that is lacking, but also the character development of the leads as well. The relationship between Ada and Gareth is disjointed and uneven, going from casual acquaintances to tortured yet unrequited lovers in the span of about two minutes. It’s unnecessary and feels a bit like a swerve in a film that isn’t wanting for a romantic B-plot. And then there’s Gareth, the audience’s guide through all of this, who is presented as a strait-laced, straight-edge, goodie-two shoes wonderkid with no defining traits aside from his dogged journalistic persistence. As a character, he works passably for the narrative, but not especially so for an audience looking to relate to someone.

Even so, it’s not all that bad. As the film moves into its final stages, Holland does a good job connecting the larger global questions about preserving Stalin as a safety valve against Hitler, famine/genocide be damned. It’s an interesting if tragic story about the gambles governments engage in when moving pieces across a massive board, and the sacrifices made not just in lives, but also in morals and ideals. Holland, and the script by Andrea Chalupa stick this point, and are aided in no small part by Norton, whose performance brings this to the fore.

So it is a mixed bag, really. Mr. Jones is a well-acted, timely, and important film that nevertheless finds itself bogged down by the larger narrative: one it has difficulty compressing down into a digestible couple of bites. Visually, there’s a color desaturation effect used to give visual texture to the scenes that take place outside of the safe spaces occupied by compliant journalists, and while this is indeed effective thematically, it wears on the eyes after a while. Like the film as a whole, it’s a great intention betrayed by spotty execution. Though unintentional, this seems fitting for a film that outlines the failures of a people’s revolution that began to fall apart almost immediately after its inception.

Comments on this entry are closed.