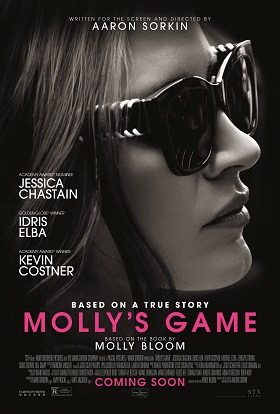

The real-life story of a high-stakes poker organizer who got mixed up in a world of celebrities, Wall Street thugs, and mafia goons, Molly’s Game has a lot going for it, not to mention a few things going against. Starring Jessica Chastain as the eponymous Molly, it boasts a robust supporting cast, a rags-to-riches ethos with celebrity outliers, and a script penned by Aaron Sorkin himself. Yet the film also has Sorkin as a director, which represents the man’s first time behind the camera, and these rookie sensibilities often shine through.

Molly’s Game opens with a voiceover by Molly, who takes a few minutes to introduce herself to the audience as a one-time Olympic-hopeful skier whose career ended with a serious injury. En route to law school, Molly takes some time to find herself in L.A. during the late 2000s, right around the time the U.S. economy crashes. Via a series of flashbacks that litter the first and second acts, the audience learns that Molly eventually gets work as the personal assistant to a local club owner, Dean (Jeremy Strong), who runs a high-stakes poker game for L.A.’s rich and famous. Since Molly takes care of all Dean’s errands, the poker game eventually becomes her responsibility, leading to a new world of big tips and celebrity hob-knobbing.

Molly is making great money and making killer connections, but gradually realizes that she can do her best work as an independent operator. This leads her to set up her own series of games, first in L.A., and later in New York. As the games and pots get bigger, so does Molly’s income, not to mention exposure (both financial and legal). By the time Molly starts getting static from the Russian mob, the feds get wind of her games, which lead to a series of legal problems for Molly that lead up to the present-day portion of the picture.

Many of the flashback sequences in Molly’s Game are born out of conversations Molly has with her attorney, Jaffey (Idris Elba), who spends the majority of the movie coaxing some sympathy out of Molly as a character. Jaffey has a hard time believing that Molly is just the victim of circumstances that spiraled out of her control: a tenuous lifeline that Sorkin’s script and movie hang onto so that Molly can remain someone the audience is willing to side with. Molly’s interactions with ruthless mobsters, Wall Street crooks, unsympathetic Feds, and a ruthless Hollywood celebrity dubbed Player X (Michael Cera) repeatedly back Molly into corners, and to the woman’s credit, she manages to get out of most of them.

It’s refreshing to see a movie with a strong female lead that not only aces the Bechdel Test, but establishes herself as a woman whose sexuality plays no part of her success (and doesn’t drive any part of the narrative). Chastain is beautiful, to be sure, but Molly’s Game goes out of its way to establish that Molly correctly views romance in her line of work as a liability, not a sought-after luxury. What she accomplishes is entirely the result of her business sense, social savvy, and hard-hearted determination. It’s an interesting tale, and Molly is a captivating host throughout the story, yet there are some small holes in the effort.

Molly’s Game is a compelling movie that has the bad luck of a year-end release, demonstrating that a sharp script, great cast, and interesting real-life bona fides doesn’t necessarily guarantee success in an Oscars/Star Wars market. It’s a celebrity-sprinkled bio pic with a poker backbone and the specter of a legal procedural looming in the distance, which give it some fun notes to play, yet not enough relevance to make any real waves in December. The Sorkin-penned screenplay means that the conversations sparkle, which they need to do in a VERY chatty 130+ minute movie, yet the overall effort suffers as a result of that same rookie director.

The movie comes together at a base level, in that Jaffey more or less tells the audience how they should feel about Molly after acting as their surrogate for roughly two hours, yet it is all a little hard to buy. The audience only ever gets Molly’s side of the story, so it is difficult to know if she’s worthy of the redemption that the film’s arc bends towards. Molly is an absorbing person with an interesting journey, yet if she’s a surrogate casino in all of this, rooting for her ultimately means one is rooting for “The House.”

Even so, Molly’s Game ends up working more than it doesn’t, largely because most of the other non-Molly players in this drama are so pathetic, evil, or violent that they stand no chance of receiving any sympathy. Since Molly gets to tell her best version of all this, and since she’s at the center of it all, it’s easy to root for her, and the narrative plays out in an appropriately agreeable way. The journey to get to this end is littered with sharp, witty dialogue delivered by a cadre of superb actors in roles both big and small. Kevin Costner even pops up in small doses, which is where he seems to do his best work these days. It all comes together, and is a respectable first try for a director with skill enough on the page to make all of this pretty damn fun.

Comments on this entry are closed.