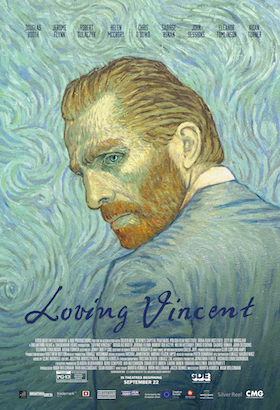

A touching tribute to one of the most famous artists in western civilization, Loving Vincent does right by Vincent van Gogh, recounting the Dutch painter’s life story in an inventive and mesmerizing way. Co-directors Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman have put together a movie that is the first ever to be assembled entirely via oil paintings on canvas, with each frame of the animated feature brought to life by the efforts of 125 artists. And while the story proceeds along familiar narrative lines, the journey to the end is littered with surprises.

The film follows something of an amateur detective route, a-la Citizen Kane, with a young man tasked with delivering a letter: an endeavor that leads to a better understanding of his subject by way of conversations and interviews. This sleuth, Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), is a reluctant participant in the quest, but is forced by his father, the local postmaster of Arles, France, to see that Vincent van Gogh’s final correspondence to his brother is delivered. Armand’s father is portrayed as a sympathetic friend of Vincent’s, who wants to do one last favor for a man that didn’t get that many breaks in life.

Admirers of Van Gogh are familiar with the Roulin family, as Armand, his parents, and siblings all sat for portraits that now represent some of the painter’s finest work. Their appearance in Loving Vincent are a harbinger for the visual palette Kobiela and Welchman utilize to tell their story, which uses landmarks from Van Gogh’s extensive repertoire, like the Café Terrace in Arles or the wheat fields of Auvers-sur-Oise, as backdrops for the film. The swirling, bold colors of the movie’s painted frames erupt in true Van Gogh style as Loving Vincent progresses, and if anyone ever wished for a movie that literally brings the man’s paintings to life on the silver screen, this is it.

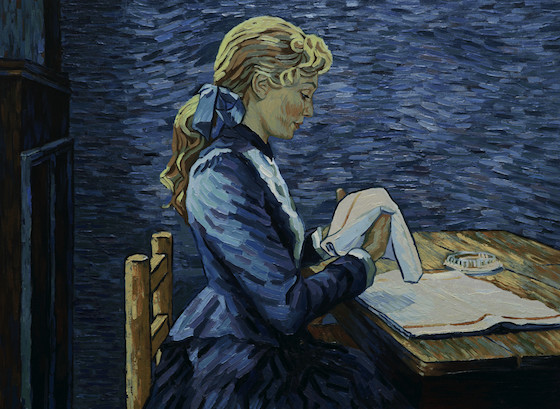

Starting off over a year after Vincent’s death, Armand goes from Arles to Paris to deliver Vincent’s letter to Theo van Gogh, only to learn that the latter man died only a few months after his brother. This leads Armand to Auvers-sur-Oise, where Vincent spent the last few months of his life, and where Armand begins to get a better handle on what Vincent was going through prior to his suicide. He meets with a local hotel proprietress, Adeline Ravoux (Eleanor Tomlinson), who speaks fondly of the artist who stayed at her family’s establishment for a time, as do a few of the other locals who accepted Vincent’s eccentricities up to a point.

Others are less kind, like Louise Chevalier (Helen McCrory), who tended to Vincent when he was a patient of Dr. Paul Gachet (Jerome Flynn). As Armand starts to get at the heart of who this enigmatic artist was, a human being starts to emerge from the fog of legend. Vincent van Gogh was a troubled man shackled to his emotions and driven by an intense passion for his art and a desire to succeed (personally and professionally). A failure at pretty much everything in his life while alive, Vincent struggled to maintain friendships, and seemed prone to mood swings that threatened his physical well-being.

What never faltered, however, was the commitment to his craft during the ten or so years that he was active as an artist, and it is that drive that captivates Armand (not to mention generations of admirers in the 100+ years since his passing). Loving Vincent takes its time developing an idea of Vincent van Gogh as the classic tortured artist, one with beauty in his heart suppressed by a tangled rat’s nest of emotions between the man and his community. As a story, it is somewhat predictable, in that there are no new revelations or surprises to be found, but for people with only passing knowledge of Vincent, it is a fine retelling of the guy’s later life.

Despite the fact that the performances of Booth, Tomlinson, Flynn, et al are buried beneath the thick swirls of the Post-Impressionist animation, the nuances of their facial and body work emerge with magnificent clarity. This is a testament to the actors as well as the artists involved, who have come together to create something truly unique. The story is, by design, confined to flashbacks throughout much of the picture, which threatens to stagnate a narrative already beset by foregone conclusions (Vincent is dead at the beginning of the picture, and his fame and renown are well known to most), yet Kobiela and Welchman do a fine job keeping things moving.

It’s a risky proposition, taking cherished pieces of art and animating them to life in a medium for which they were not intended, yet it is a gamble that pays off in Loving Vincent. The settings as presented in Arles, Paris, and Auvers-sur-Oise explode to life with a vivid, tangible presence that transports the viewer into Vincent’s world. For the people that are fans of the artist’s work, it is a trip into a universe that they have only experienced at a distance, and with the help of an active imagination. The scenes in Loving Vincent move with an organic presence that ably transpose impasto techniques into a non-static template, and adds a layer of emotion to Van Gogh’s work that might not have seemed possible before this.

Opening this week at Tivoli Cinemas, Loving Vincent is sometimes a bit flat with its narrative thru-line, yet more than makes up for this with its earnest and engaging approach to discovering what drove Vincent van Gogh as a man and an artist. For those unfamiliar with Van Gogh’s story, it is a faithful exploration of the person behind the paintings, and for those already acquainted, it is a thrilling stroll through the world heretofore known only on a canvas or flat page.

Comments on this entry are closed.