[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down]

[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down]

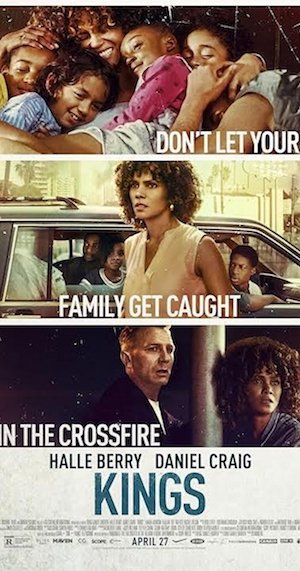

A clumsy assemblage of characters and moments that flirt with authenticity and relevance, Kings, opening in theaters tomorrow, is a movie that has an idea of what it wants to be, yet can’t seem to put the pieces together to make it work. A fly-on-the-wall tale of inner-city Los Angeles just before and during the 1992 riots, the movie wants to tell a story that works on both the micro and macro level, yet fails to do either. The result is a film that takes a big swing, yet misses out on humanizing the people and the city that have woven themselves into the larger narrative of late-20th century American history.

In Kings, Hallie Berry stars as Millie, an overworked single woman who lives in a rough part of 1992 L.A., and is fostering at least half a dozen kids ranging from toddler to teenager. Overwhelmed and struggling to make ends meet for her adopted brood, Millie comes off as big-hearted yet spread much too thin. And while one of her older adopted wards, Jesse (Lamar Johnson), helps with the younger kids, there’s just not enough attention to go around.

Although Kings sets itself up as a movie about Millie, and to a certain extent, her wild-eyed neighbor Obie (Daniel Craig), much of the picture concerns itself with Jesse and his foster siblings. Jesse is a young teenager who is struggling with his hormones and his place in Millie’s house as the de facto co-parent. On top of this, he also has to contend with the very tricky proposition of growing up as an African-American man in one of the most racially and socially turbulent times/places in history. This intersection of adolescence and early-90s L.A. culture makes for a potentially interesting story due to the aforementioned factors, but also because Jesse’s character is the most fleshed out in the script.

Yet this is where the cracks in the production begin to show. Johnson does a serviceable job with his role, yet the young actor strains under the weight of the film’s more dramatic moments. Although he shares a number of scenes with Berry, the majority of his screen time is spent with younger, less experienced actors that don’t do him many favors, and Kings suffers as a result. All of this hobbles the attempts to weave Jesse’s coming of age story into the larger framework of the riots, which gives the movie a disjointed, incomplete, and half-baked feel.

Yet this is where the cracks in the production begin to show. Johnson does a serviceable job with his role, yet the young actor strains under the weight of the film’s more dramatic moments. Although he shares a number of scenes with Berry, the majority of his screen time is spent with younger, less experienced actors that don’t do him many favors, and Kings suffers as a result. All of this hobbles the attempts to weave Jesse’s coming of age story into the larger framework of the riots, which gives the movie a disjointed, incomplete, and half-baked feel.

Writer-director Deniz Gamze Ergüven made a splash at Cannes a few years ago with her debut feature, Mustangs, yet the advantages that bore that movie to an Oscar nomination are absent here. Ergüven, a native of Turkey, clearly had a handle on the language and culture of the Turkish-set Mustangs, yet that’s just not the case with Kings. The dialogue, bearing, and attitude of the latter film’s characters doesn’t ring with the authenticity that’s needed to tell this kind of story. Indeed, despite all the intercut footage of Rodney King’s trail into Kings, this disconnect between the time/place and what’s seen on-screen is vast, which make these newsreel moments feel more like telling than showing.

There’s also a confined, narrow aspect to the whole effort, which rubs awkwardly against the real-world familiarity many American audience members will bring to Kings. L.A. is a vast, sprawling landscape that’s been generously filmed over the years, yet it only gets to peek out from the corners, here. Undoubtedly due to the modest budget and the fact that the movie is a period piece (wide shots would likely be stocked with anachronistic automobiles and architecture), Kings never really gives its audience a sense of the city, robbing it of a true sense of place. For example, a harrowing drive through the heart of the riots late in the film is obscured by heavy smoke, leaving just the passengers in-shot to convey the chaos of the moment (with varying levels of success).

Berry and Craig, both outstanding actors, do their best to fill in the gaps of the thin-soup script, yet their performances tend to veer into the broad more often than not. Whether it is the result of deliberate direction, or because the script hamstrings them thus, the result is a pair of performances too often dialed all the way up to 10. This, paired with the somewhat shaky work of the younger performers, pulls the overall effort down and robs the story of the nuance required to tell a story as socially and racially complex as this one.

Berry and Craig, both outstanding actors, do their best to fill in the gaps of the thin-soup script, yet their performances tend to veer into the broad more often than not. Whether it is the result of deliberate direction, or because the script hamstrings them thus, the result is a pair of performances too often dialed all the way up to 10. This, paired with the somewhat shaky work of the younger performers, pulls the overall effort down and robs the story of the nuance required to tell a story as socially and racially complex as this one.

The end result of all of this is a thematically grounded movie with competing narratives and a disjointed identity that feels less like a genuine dramatic reading and more of a strained imitation. There’s good intentions behind Ergüven’s effort, yet there’s just too much missing from the story and the characters to provide Kings with the authenticity it so desperately requires. Opening this week, the film is a valiant attempt to tackle a timely and important moment and place, yet Kings never quite finds its crown.

Comments on this entry are closed.