[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

A courageous attempt at spiritual exorcism by way of cinematic scripture, Honey Boy would be worth seeing even if it wasn’t well assembled and/or emotionally engaging. Here’s the thing, though: the movie works, and well. Based on the adolescence and young adulthood of Shia LaBeouf, who wrote the script as a therapeutic exercise, Honey Boy crackles with the pain and depth of a scribe pinning their heart to the wall.

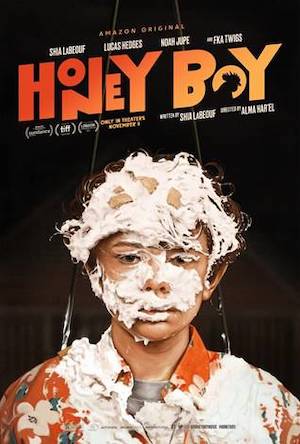

Honey Boy is broken into two time periods: 2005, where Lucas Hedges plays a version of LaBeouf named Otis during his career breakout, and 1995, when the pre-teen (played here by Noah Jupe) is just getting his start in the business. Hedges portrays the 2005 version of Otis as a bundle of anxiety, fury, and self-destructive Id, while the ’95 portion endeavors to show how an earnest, talented young man came to be this way. The answer isn’t long in coming once the audience meets Otis’ father, James (played by LaBeouf), a jumpy ex-con and Vietnam veteran with more insecurity than love in his heart.

Honey Boy bounces between these two timelines as Otis is asked to dig up the memories of his childhood during a stint in rehab. It’s not an easy ask. Defensive, confrontational, and entirely convinced that all of the pain feeding into these 2005 traits are a vital component of what makes him a successful actor, Otis wades through a tangle of childhood trauma with no small amount of reluctance. The memories he has of his father during his formative (1995-ish) years are complicated and reflect a young man whose fierce love of his father is matched only by his fear of the man’s dark side.

The 1995 section shows Otis working hard as a young actor with promise while James, a has-been (never-was?) rodeo clown looks on with a mixture of pride and resentment. These emotions are not mutually exclusive, and bleed into each other when the father and son spend their time together in a dingy L.A. motel. The audience comes to learn that James actually works for Otis as his official handler/guardian, and the imbalanced power dynamic is sometimes too much for the father to bear.

It’s impossible to know just how much of what’s on screen is a genuine reflection of LaBeouf’s life, though taken on its face, it all lines up. As James, LaBeouf appears to be tapping into a deep well of experience that transcends mimicry, and instead seems to be striving to make sense of the man who clearly shaped the person “Otis” would become. Fiercely protective of his son, yet incapable of publicly displaying anything resembling honest affection, James is at war with himself at all times: with his son acting as the collateral damage caught in the middle. Indeed, there’s a scene in Honey Boy where Otis has to literally be a middleman between his feuding parents, and it comes as close to capturing the essence of who LaBeouf is as a person and actor as anything in the picture.

Structurally, although the shifts between 1995 and 2005 are halting at times, the moves between these two periods of Otis’ life work well as a reflection of the elder version’s struggle to dredge up the memories that have informed his transition into adulthood. Painful recollections are often buried beneath layers of protective blank spots, and Otis’ journey to find the connective tissue between his childhood and 2005 self comes in patches that reveal only fragments at any given moment. And while Hedges does fine work as the fully-grown version of Otis, it is Jupe and LaBeouf that do a majority of the heavy lifting throughout Honey Boy.

Jupe plays the quiet moments with a contemplative air of wise-beyond-his-years posturing that speaks to his immense talent as an actor. LaBeouf is mesmerizing as the angst-ridden patriarch who always has a speech ready or an outburst loaded for launch, yet the film works because Jupe is able to absorb this chaos and translate it into silent expressions and body language that is no less informative. Director Alma Har’el keeps her shots tight and handheld in many of the scenes between the two, enhancing an already claustrophobic vibe that runs through much of the film. Indeed, whether he’s trapped on the set of a big-budget blockbuster, kids show backlot, or run-down motel room, Otis is trapped in a prison of his “success”: his father the only reprieve from the isolation.

When that one lifeline is a professionally impotent, socially castrated, and emotionally barren man who ekes out just enough humanity to keep his son coming back for more, it’s easy to understand how LaBeouf might have grown into the man any audience with internet access knows today. Bullied by a father who demanded a son’s success to sustain himself, and living with the resentment that this brought, LaBeouf has given over a very tender, exposed part of himself with all of this. Addiction issues, self-esteem trauma, and trouble processing his emotions in a healthy way all follow from what’s put on display in Honey Boy, and it’s something to behold.

Har’el makes good use of the script from a visual standpoint as well, using natural sunlight to underscore the healthier portions of Otis’ life while flat, neutral colors define the more difficult portions. But it’s the dueling performances of LaBeouf and Jupe that power this film and elevate it beyond anything resembling a self-serving vanity project. Honest, raw, and fueled by memories that seem to have fought their way to the surface through considerable resistance, Honey Boy is a film that helps make sense of LaBeouf, sure, but works just as well as a treatise on the resiliency of love in the most difficult of circumstances. And while it’s too bad LaBeouf had to suffer so much to create this, if that pain did nothing else, it helped inform one hell of a good movie.

Comments on this entry are closed.