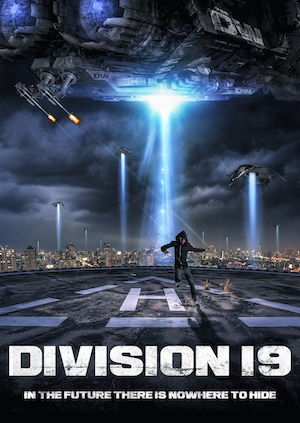

[Rating: Rock Fist Way Down]

The pitch for Division 19, in theaters and available on demand tomorrow, must have been something like “The Hunger Games meets The Truman Show with just a hint of V for Vendetta,” which on the face of it sounds fun, sure. Yet while Division 19 is many things (narratively inconsistent, badly paced, nonsensical, uninteresting), the one thing it isn’t is a good time. And while writer/director S.A. Halewood appears to have approached this with good intentions, it seems obvious that the film made a lot more sense in her head than it does on-screen.

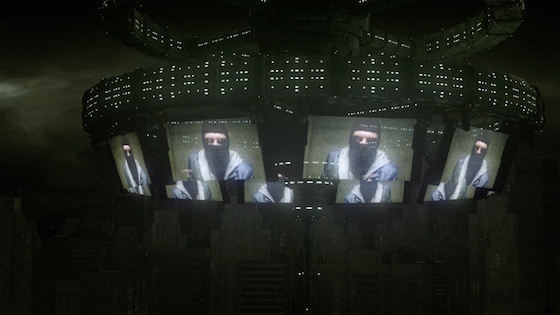

Just minutes into Division 19, on-screen text explains that the year is 2039, anonymity is a crime, and anyone who remains unregistered risks ‘disappearance.’ What’s more, convicts serve as popular entertainment for the masses, with Netflix and Instagram supplanted by closed-circuit broadcasts of prisoners eating, sleeping, and even fighting for the pleasure of audiences around the world. These prisoners are the influencers of 2039 and are commoditized by the Big Brother-esque government accordingly. The cigarettes or clothes of popular prisoners sell like hotcakes, and no prisoner wields more advertising power than Hardin Jones (Jamie Draven).

Hardin’s kid brother, Nash (Will Rothhaar), is part of an off-the-grid resistance cell looking to shut down not just this prison-T.V. enterprise, but the corrupt government behind it as well. When Nash and his comrades engineer a prisoner escape to spring Hardin, they’re doing so as part of a larger plan to bring down the whole system. As far as set-ups go, all of this scans and ties in well with a rising contemporary fear related to the proliferation of tracking technology in smart devices. Yet Division 19 can’t help but to keep stepping on its own foot, contradicting the rubrics it lays out for itself or outright ignoring the logic of its conceit.

For starters, the rules of this world aren’t consistent. Division 19 wants the audience to believe that this takes place in a high-tech surveillance future on steroids, yet when the most famous person/fugitive in the world is spotted on the streets, he’s able to just outrun pursuers, drones, and cops by ducking into a bar. What’s more, if everyone is “chipped” with a tracking device as the film takes the time to establish, why does it take Big Brother more than 5 minutes to find anyone?

And this is just the surface level narrative stuff that jumps out while watching all of this. If one wanted to go deeper, they might ask why all the people in the resistance only move via parkour, or why two actors playing brothers have noticeably different regional accents. Most of the characters exist in Division 19 solely for exposition purposes, like the head of the prison T.V. network, Neilsen (Alison Doody), so it stands to reason that some of them would explain this stuff in a couple of throwaway lines.

This is very much not the case, however. Instead of building this world out to explain these irregularities, Halewood opts to linger on contemplative close-ups for what feels like ages for no apparent reason other than to squeeze in an increasing number of hand-held shots. And holy shit, there is a lot of hand-held camera work for no good reason whatsoever in this thing.

The character work is even more shaky than the cinematography, however. There’s no reason to root for anyone in Division 19 other than the obvious good vs. bad dynamic the film keeps cramming down the audience’s throat. The villains are so irredeemably evil that they turn into live-action cartoons, while the heroes do little to endear the audience to them aside from not being on the wrong side of this heavy-handed narrative. A romance sub-plot is tossed into the middle of the film with all the thought and deliberation of a falling leaf, adding another story thread to a movie that can’t handle the sparse few it is already juggling.

So, what begins with an intriguing premise devolves into an ill-conceived world-building exercise stocked with incomplete characters, bad camera work, poor narrative logic, and rotten pacing. Halewood seems to have something interesting to say about the rise of surveillance culture and the commodification and exploitation of society’s most vulnerable, yet the script can’t seem to keep up with these intentions.

As it stands, Division 19 just kind of floats along on the vapors of an interesting premise without setting down to sink roots into anything substantial. Aside from the shaky-cam shots, the film does look good, and the costumers and set designers deserve some credit for creating the illusion of dystopia. It’s the script that needs another coat of paint, or an extra few patches, though, for the holes in it are big enough to drive a surveillance truck through.

Comments on this entry are closed.