[Rating: Rock Fist Way Up]

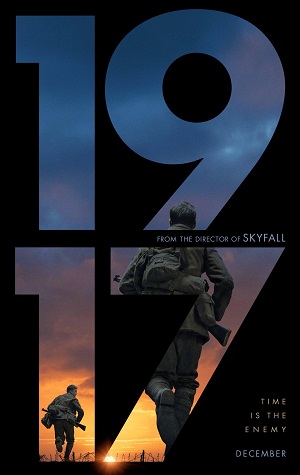

Tense, gripping, beautiful, and brutally relentless, director Sam Mendes has achieved something extraordinary with his newest feature, 1917. A classic behind-the-lines action flick set during World War I, the story is concerned not just with the mission at hand, but eternal questions of sacrifice, honor, duty, and what remains of both the living and the dead after the last shots are fired. The result is a movie that is equal parts moving and mesmerizing, aided in no small part by a technical achievement that would be astonishing by itself even if it didn’t substantially contribute to the effort (which it unquestionably does).

Lance Corporals Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Schofield (George MacKay) are resting behind the lines in France circa April 1917 when they get orders to report to General Erinmore (Colin Firth). Erinmore explains that the Germans opposite their trench have cleared out of their position in what appears to be a full-scale retreat, yet aerial reconnaissance shows that it is little more than a feint designed to draw the English into an ambush. Blake’s older brother is part of a battalion that’s scheduled to exploit this “retreat,” and without phone lines connected, the only way to call off the attack is to send runners to personally deliver the message.

Erinmore tasks the pair with making the trip through no-man’s-land to call off the assault, hoping that Blake’s desire to save his brother will be motivation enough to get the difficult job done. The mission isn’t without considerable danger, however, for even with the bulk of the German army moved off the line, barbed wire, booby traps, rearguard elements, and a host of other deadly obstacles stand in their way. And while Blake doesn’t waste a second when receiving his orders, Schofield, the more experienced soldier, stresses caution and explains that they will have to be “clever” to get to their target.

Much has been made of Mendes’ decision to present 1917 as a series of long tracking shots stitched together by crafty editing, and the film certainly lives up to the buzz. There’s only one deliberate cut in the film, and while others do occur during low-light location transitions, they are indeed few and far between. This is no mere gimmick, however, as the audience is forced to live every second of this journey with Blake and Schofield, who rarely get a moment of peace throughout the whole ordeal. The sense of urgency and intimacy is palpable as a result, pulling the audience into this maelstrom like paper caught in a hurricane.

From a technical standpoint, every facet of this film’s production meets the highest possible standard of evaluation. The costuming and make-up work are flawless, yet even these triumphs pales in comparison to the Herculean effort that must have gone into the set design, with acres of trenches, tunnels, bombed-out villages, and dugouts meticulously designed and presented, here. Nothing seems out of place in any shot, from the bodies in various states of decomposition littering the “hot” areas, to the fragments of a French community long-since corrupted and scattered by the war to end all wars.

And then there’s the cinematography by Roger Deakins, who has reteamed with his Skyfall collaborator here to present some of the most hauntingly beautiful images ever put to the screen. The logistics of mapping out the long takes of the film (and hiding any tracks or equipment) must have been mind-boggling, yet that didn’t stop Deakins from crafting a visual feast that contends with night, day, smoke, water, and even an aerial sequence. 1917 features a great deal of ugliness born out of the cauldron of war, yet it still manages to take its audience’s breath away with shots that are nothing short of remarkable (a raging fire near the midway point is particularly striking).

Chapman and MacKay both do outstanding work in the leading roles, as do a host of supporting actors that drift into the movie only to then fade out again. One scene early in the picture finds Blake and Schofield haggling with a war-weary lieutenant (Andrew Scott) who refuses to believe that the Germans have moved off, yet agrees to help the film’s heroes all the same. Although the words “shell shock” or “battle fatigue” are never spoken, there’s a running theme throughout 1917 dealing with the psychological effects of warfare that touch even the toughest soldiers, and this encounter is one of several moments that illustrate the different ways the conflict has crippled these men.

And while 1917 isn’t for the faint of heart (like, seriously: anyone watching this needs to prepare for full-on white-knuckle mania lasting a rock-solid 115 minutes), it’s well worth the time and endurance. Aside from the technical achievement of the set-up, Deakins’ camera work combined with career-best performances from all involved puts this one in a unique class that few films this century have approached. World War I, the war to end all wars, did nothing of the sort, yet 1917 may well go down as the movie to end all war movies, as it’s hard to imagine anyone topping this one.

Comments on this entry are closed.